Abstract: In the late nineteenth century, off-reservation boarding schools became the instrument of choice for the United States federal government to assimilate Indigenous communities. By separating Native American children from their families and placing them in government-operated schools, white officials hoped to transform them culturally, politically, and economically. Although the system was reformed in the early 1930s, boarding schools continued to promote assimilation for several more decades. In fact, white officials even developed new methods to assimilate young Native Americans, including the use of substitute currency, or scrip, as a form of economic training. One of the first off-reservation schools to adopt a scrip system was Sherman Institute in Riverside, California. In November of 1933, school administrators introduced a system of paper money to teach the school’s Native American pupils about life in a capitalist society. Through an analysis of scrip, this essay explores what Indigenous students at Sherman Institute learned about capitalism during the 1930s. Specifically, the article analyzes how the scrip system replicated the US economy with individual consumption at its center in an effort to communicate specific values, and how Indigenous students navigated said system. Thus, this essay argues that administrators at Sherman Institute used scrip to transform school life in a flawed attempt to present an idealized form of consumption-based capitalism to young Native Americans.

Starting in the fall of 1933, the Native American students attending the government boarding school Sherman Institute in Riverside, California, were paid for their school work in a form of substitute currency referred to as scrip. By using this money, students were expected to learn through direct experience how the American economy worked and how they were supposed to operate within it. Like previous generations of students at Sherman Institute and other government-operated schools, pupils were taught that capitalism was superior to the economic systems of their Native American communities. In this new system, however, economic education was no longer a piece of the school curriculum; it became the overarching principle around which everyday life was organized. As something that students earned during school hours and spent in their leisure time, scrip affected virtually every aspect of life at Sherman. The money that students earned for work done in class could be used on the school campus to pay for necessities the school provided, such as clothing, as well as for luxury items like refreshments from the student store or tickets for school events. As they used scrip, students were expected to adopt certain behaviors and values that officials considered essential to life in a capitalist economy, but they also found ways to circumvent the school’s restrictive understandings of how economies should function. While the use of substitute currency in Indian schools became national policy, Sherman’s scrip system—in addition to being one of the first—was one of the most elaborate.

The existence of a scrip system at Sherman Institute in the 1930s raises important questions about the way off-reservation schools taught young Native Americans about capitalism. In this sense, scrip shines light on a specific facet of American imperial policy: the effort to spread capitalism and transform Indigenous economies. This is particularly significant considering that Sherman Institute’s students primarily came from communities in California and Arizona that combined Indigenous and capitalist economic practices, such as those on the Hoopa Valley Reservation in Northern California (Cahill 175-82). Moreover, as Brian Gettler’s work on the adoption of currency by Indigenous nations in Canada illustrates, the adoption of money involves a reconfiguration of sociopolitical relations (4). Thus, it is important to understand how the American government actively encouraged Native American communities to adopt a dollar-based economy through policies like the scrip system. This essay argues that administrators at Sherman Institute used scrip to transform school life in a flawed attempt to present an idealized form of consumption-based capitalism to young Native Americans.

This analysis of Sherman Institute’s scrip system is laid out as follows. The first section addresses the essay’s use of sources as well as its theoretical underpinnings. The second section builds on previous scholarship to briefly discuss the origins of federal Indian education and the way schools taught economic issues prior to the 1930s. The third section discusses the workings of the scrip economy and its parallels to the American economy at large. The fourth section provides insight into the ways in which students subverted the expectations of white officials in their use of scrip, while the fifth section analyzes what students were expected to learn about their place in the US economy by using scrip. The final section explores how the scrip economy functioned as a consumer society and what the emphasis on spending meant for the school’s overall program of assimilation.

Theoretical Framework

This investigation of Sherman scrip is based primarily on historical documents from the collections of the Sherman Indian Museum and the US National Archives. The most important sources in these archives include letters, superintendent reports, and school publications. First, correspondence from Donald Biery, Sherman Institute’s superintendent during the 1930s, contains important clues about the perspective of white officials who operated the scrip system. Second, annual reports from this period indicate how these officials evaluated scrip and how it fit the larger goals of both the school and the federal government. Lastly, both the school newspaper, the Sherman Bulletin, and yearbooks provide glimpses of scrip’s everyday use and student experiences with the system, although such accounts typically echoed school rhetoric (Bahr 28). Generally, these sources offer an impression of the past that is fragmented and informed by the interpretations of white authorities. Nevertheless, by bringing these disparate sources into dialogue with one another, they offer insight into the ways different historical actors used scrip to their advantage.

Although the available sources make an in-depth analysis of student agency difficult, it is possible to uncover at least part of their experience. As historian Tsianina Lomawaima argues in her account of the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma, “[m]uch of student life was unobserved by and unknown to school staff or administrators” (29). Even in the absence of explicit student testimony, then, it is safe to assume that scrip was no exception. To make sense of the ways in which students used scrip for their own purposes, the notion of ‘turning the power’ offers a useful framework. Taking an idea that exists in various Indigenous cultures, Trafzer, Keller, et al. introduced this concept into the academic debate to conceptualize how boarding school students improved upon a predominantly negative experience (1). Students used what they had learned in colonial institutions to their advantage and defied the expectations of white officials. Therefore, the idea of ‘turning the power’ represents both resistance and resilience, as Native Americans created spaces within hostile environments where they could thrive. Ultimately, the concept serves as a reminder that even in those instances where historical sources are silent on the realities of student experiences, Native youths tended to be more resourceful than white authorities would have given them credit for.

Historical Background

Sherman Institute first opened its doors in 1902 as the last of twenty-five federal off-reservation institutions for young Native Americans. Under the auspices of the Office of Indian Affairs, the American government had begun building a network of on- and off-reservation schools in the 1870s. Even though officials presented education as a form of charity that was supposed to help Native Americans integrate into US society, historians argue that new policies were in fact “part of a continuum of colonizing approaches” (Jacobs 25) intended to break up Indigenous communities and take their land. The first off-reservation institution was Carlisle Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which opened in 1879. Army captain turned school Superintendent Richard Pratt ran Carlisle like a military institution where students wore uniforms and marched to classes in which they acquired labor skills and were taught rudimentary academics (on Carlisle, see Fear-Segal; Fear-Segal and Rose). The school’s extracurricular program consisted of music, sports, and other activities that further immersed students in Anglo-American culture. Despite administrators’ attempts to control every aspect of school life, however, students found ways to resist and managed to make school life tolerable, if not pleasant (Adams 223). Significantly, harsh punishments rarely deterred students from practicing their own cultures in private, especially if they attended school with siblings or cousins, as was often the case.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, institutions modeled after Carlisle opened across the American West. Even as these schools adapted to local circumstances and the philosophies of their staff, they all implemented a strict English-only policy, military discipline, and a curriculum centered on labor training. This was also true for the Perris Indian School, the first off-reservation boarding school in Southern California, which opened in 1892 and was replaced by Sherman Institute in 1902 (see Trafzer and Loupe). The new school was located on the outskirts of Riverside, near Los Angeles, an area that has historically been home to Cahuilla, Serrano, and Tongva communities. Initially, Sherman students came mostly from these and other nearby communities, but enrollment quickly expanded. By 1909, the school was home to 550 students from forty-three different communities, and the student body continued to grow, reaching a population of 1,277 by 1930 (Bahr 20). The majority of these students came from communities across California and Arizona, with children from Hopi, Navajo, and local ‘Mission’ communities attending in particularly large numbers during the school’s early decades (“Sherman Bulletin” 1928 1). Even though Carlisle closed in 1917, Sherman Institute and other schools thus continued to carry out its agenda of cultural assimilation.

Over the course of the 1920s, there was growing criticism of both the policy of separating children from their parents and the way these schools were run. As the chasm between rhetoric and reality widened, reform seemed inevitable, which was underlined by a scathing report on Indian policy published in 1928. Based on their inspection of several off-reservation schools, the investigators concluded that “the provisions for the care of the Indian children in boarding schools are grossly inadequate” (Meriam et al. 11). Disease, child labor, and inadequate training were just some of the problems they cited. In response, the schools abandoned their military systems and made efforts to provide a more culturally appropriate education. For the first time, the government formally allowed Indigenous youth to choose for themselves whether and to what extent they wanted to adopt American culture (Lomawaima and McCarty 73). Another important change was the decision to restrict school enrollment and have off-reservation schools target specific areas; as a result, Sherman Institute could only enroll new students from California and western Arizona in the 1930s and 1940s. However, despite various reforms, Native children continued to attend schools with a Eurocentric curriculum at great distances from their families well into the 1960s.

Given their long history and lasting impact on Native American communities in the United States, it is no surprise that these schools have received significant scholarly attention over the past three decades (see Whalen, “Finding” for an overview). Among the notable works are both studies of the education system as a whole (e.g., Adams; Coleman; Reyhner and Eder) and of individual institutions (e.g., Lomawaima; Vuckovic; Gram), including Sherman Institute (e.g., Sakiestewa Gilbert; Trafzer, Sakiestewa Gilbert, et al.; Bahr). At the same time, historians have also focused on specific facets of boarding school life, including health (Keller), sports (Bloom), and music (Parkhurst), in an effort to better understand the lived experiences of cultural assimilation.

One particular aspect of the education system that has received considerable attention is labor training. Here, scholars have built on insights from studies on Indigenous engagements with the capitalist labor market (see, e.g., Littlefield and Knack; Hosmer and O’Neill; Williams). As Indigenous wage labor became increasingly prevalent by the early twentieth century, aspects of the capitalist economy were incorporated into Indigenous economic life, resulting in hybrid economies (O’Neill 12). Native Americans increasingly worked off the reservation but devised economic strategies that allowed them to avoid full assimilation into American society (Cahill 199). Boarding schools played a key role in the government’s efforts to push Indigenous communities toward greater participation in the US economy. Littlefield, for instance, argues that students “learned to labor” for the benefit of the American market based on the fact that boys spent most of their time in school training to be printers, tailors, and other jobs that did not exist on reservations, while girls were prepared for domestic tasks, such as sewing and cooking (46). A central component of vocational training at many off-reservation institutions was the so-called outing program, in which students worked for local families and businesses to gain work experience and earn a small income (Trennert; Whalen, Native Students). Although schools offered academic classes, debate societies, and marching bands, boarding school education scarcely prepared young Native Americans for more than a marginal working-class existence on the fringes of white society.

Whereas historians have studied the place of labor in the boarding school curriculum in detail, they have paid less attention to how students learned to spend money. Generally, in studies of Native American labor, scholars rarely address Indigenous consumption patterns beyond the colonial period (Harmon et al. 709). Similarly, boarding school historians have focused on the ways in which schools trained students to become laborers rather than consumers. One notable exception is David Adams, who provides some insight into the ideological underpinnings of economic education and what students learned about spending. Specifically, Adams argues that schools taught a “gospel of possessive individualism” (22). Although he does not further elaborate on this term, the central idea that in liberal democracies “human society is essentially a series of market relations” (Macpherson 270) resonated with the boarding school program. Students were taught to see themselves as individuals whose identity is defined first and foremost by their relation to privately owned material wealth. Indeed, these ideas were often communicated explicitly, for example in speeches and school newspapers (Adams 155). Aside from Adams, few scholars have paid attention to the ways in which capitalism shaped everyday life at schools like Sherman Institute. This essay addresses this research gap by analyzing the scrip system, which represented a uniquely well-structured and all-encompassing effort to imprint students with a sense of capitalist identity.

The Scrip System at Work

To understand how the scrip economy affected daily life at Sherman Institute, it is worthwhile to explore how currency circulated within the school. Scrip was first introduced at Sherman Institute in November 1933 as a reward for the work that students did in their vocational classes (“Sherman Bulletin” Nov. 1933 1). Because all scrip was paper money, scrip bills originated in the school’s printshop, which students operated under the supervision of printing instructor Judson Bradley (e.g., “Sherman Bulletin” Feb. 1938 6). Once scrip was printed, it was stored in Sherman Institute’s central administrative office. On the school level, there was at least one instructor in charge of administering scrip, who operated under the supervision of Superintendent Donald Biery and was aided by a committee of other staff members (“Records”). In addition to a central administration of the total flow of currency, each instructor served as paymaster for his or her students and was responsible for recording their ranks and the wages they received. In addition to the central office, the school had several other faculty buildings, where pupils received their wages every Friday after class (“Sherman Bulletin” Sept. 1934 2). Scrip spent on supplies provided by the school returned directly to the administrative office, whereas scrip paid to other students, for example in the barbershop, continued to circulate.

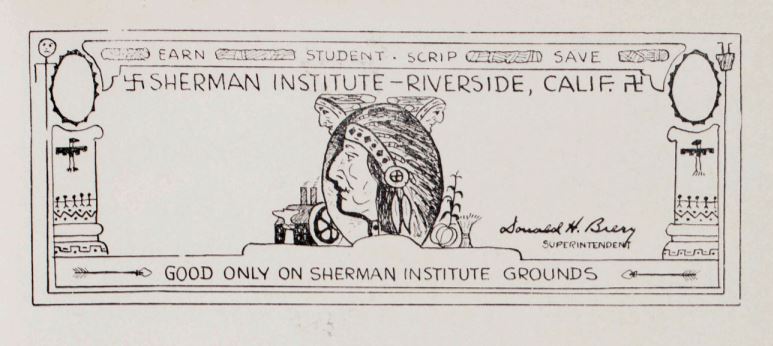

Once teachers handed out money to students during pay day, it was theirs to spend or save as they saw fit. In the process of making decisions about how to use the currency in their possession, however, students acted according to the written and unwritten rules of the scrip economy. Perhaps the most obvious activities associated with scrip were saving and earning, as both were inscribed at the top of each scrip bill (see fig. 1). This way, scrip reminded students to work hard and accumulate wealth for future use (“Purple and Gold” 1935). Because scrip existed within a larger economic system, the currency also invited a third activity: spending. Scrip bills were just pieces of paper until they were used to purchase commodities, so students could either engage in monetary transactions or set money aside with the intention of future use. Overall, pupils seemed to take the encouragement to save seriously, even more so than school officials had perhaps foreseen. By the second month that the system was in place, staff intervened to ensure that students kept spending. In an effort to keep scrip in circulation while simultaneously encouraging thrifty behavior, school officials organized a weekend trip for boys to bid on in order to “turn the accumulated scrip into circulation again” (“Sherman Bulletin” Jan. 1934 2). By slightly adjusting how scrip could be used, school officials nudged students to spend their earnings in a manner deemed appropriate to capitalist society. As discussed below, however, students did not always act accordingly.

Figure 1. The reverse of a scrip bill, as reproduced in the 1936 Sherman Institute yearbook (“Purple and Gold” 57).

The fact that the scrip economy prompted specific behavior was particularly significant because staff devised the currency as a simulation of the United States economy. Specifically, scrip replicated both the American monetary system and its market economy. Scrip was counted in cents and dollars, and its denominations also resembled the US dollar, with bills of 1, 2, 5, 25, and 50 cents, as well as 1 and 2 dollars. Additionally, the money’s design echoed the dollar in its overall layout and was adorned with Biery’s signature to lend the currency an air of legitimacy. Instead of government buildings and historical figures, however, scrip featured geometric shapes and other iconography that white officials associated with ‘Indianness.’ Significantly, the design took symbols like the ‘whirling logs’ (resembling a swastika) out of context, erasing their cultural specificity and combining them with a caricature of an Indian in a feather headdress (fig. 1). In this regard, the design of scrip illustrates the ethnocentric lens through which Sherman officials viewed Native American cultures. Moreover, the positioning of the Indian figure between a bundle of wheat and a factory resonates with the hope that students would not return to the reservation after graduating from Sherman Institute. Drawn in profile, the figure appears to be turning away from a rural past to face an urban future. This way, scrip communicated the school’s vision for the future of their students, pointing in the direction of white capitalist society both symbolically and materially.

Similarly, the earning and spending of scrip followed the logic of the American market economy. As Superintendent Biery described in a letter to Mrs. H. A. Atwood on 21 February 1934, students, like regular workers, made money by the hour, were judged on individual merit, and if they improved the quality of their work, they essentially earned a raise. Based on their skill level, students would be classified as ‘foremen,’ ‘journeymen,’ ‘apprentices,’ or ‘helpers’ (“Sherman Bulletin” Nov. 1933 1). Although some departments used different terms, a version of the four-tiered system appears to have been implemented for all students. The first school year that scrip was used, helpers earned 23 cents per hour, apprentices 26 cents, journeymen 28 cents, and foremen 30 cents (“Records” 2). Although it is not entirely clear how school officials determined these wages, they apparently modeled their rates after real dollar wages, which were around 33 cents per hour in 1933 (United States Dept. of Commerce 7). Significantly, however, many students earned wages well below average after graduation (Whalen, Native Students 108), indicating a key discrepancy between the scrip economy and its real-world counterpart. Wages were adjusted downward at least once but stayed in the same range throughout the 1930s. According to the 1935 Purple and Gold yearbook, for example, helpers earned 22 cents, apprentices 24 cents, journeymen 26 cents, and foremen 27 cents (58). What never changed was the encouragement that students received to improve their skills in order to move up a rank and earn a raise—or, conversely, keep up their work to avoid being demoted.

Taking the 1933-1934 school year as an example, vocational work for both boys and girls in most trades consisted of two 3.5-hour classes each day, meaning they spent 35 hours every week earning scrip. As such, helpers would receive $8.05 every Friday, while foremen made $10.50 each week. Even with regular expenditures, students were able to save a considerable portion of their income, as indicated by the fact that some had as much as twenty dollars in scrip at their disposal by the end of the first month (“Sherman Bulletin” Jan. 1934 2). Prices were usually advertised on site, but occasionally the vocational shops detailed their prices in the school newspaper as well. In 1933, for example, a haircut at the barbershop cost 25 cents in scrip (“Sherman Bulletin” 1933 3), while hair and scalp treatments in the cosmetology department cost 40 cents in 1938, or 3 dollars for twelve treatments (“Sherman Bulletin” Apr. 1938 6). Snacks and school supplies would have most likely cost a similar amount, whereas expenses like room and board were presumably more costly, as was the case at Salem Indian School in Oregon, where students paid 18 dollars in scrip for board each month in 1937 (“Charles E. Larsen” 41). Superintendent Biery also wrote that in 1934, board cost $4 in scrip, individual rooms 40 cents, and “food for parties and socials” 25 cents (“Records” 2). Most importantly, the scrip system gave students a range of spending opportunities that mirrored the government’s vision of US society. Whether students who returned to the reservation would have the same access to manicures and makeup salons—or even have the means to afford such luxuries—seemed of little concern.

Even though the system resembled the free market economy of the US in its setup, school staff closely monitored every aspect of it to ensure that scrip worked as intended. Regulation seems to have been the responsibility of school staff on the scrip committee, and Superintendent Biery compared their interventions in the scrip economy to the role of the American president. In his 1934 letter to Mrs. H. A. Atwood, he wrote: “Like the President adjusting the value of the dollar we have had to raise some rates of pay and raise the cost of some articles” (“Records” 2-3). The parallels to the US economy did not stop there, because Sherman staff also acted like a central bank, regulating the flow of scrip. When the circulation of scrip was at risk, they asked the printshop to create new bills or incentivized students to adjust their spending habits. Whether school staff made these parallels to federal economic policy explicit to students is unclear, but it is undeniable that they made a conscious effort to replicate national patterns. This way, students were supposed to experience the economic system as white officials believed it should function. Whereas students came from communities that blended white and Indigenous economic practices, scrip allowed little room for alternative cultural influences, approaching economic modernity as a zero-sum game.

Flipping the Scrip(t)

Despite the school’s best efforts, students found ways to approach the scrip economy with creativity and to use the substitute currency to ‘turn the power.’ Indeed, there appears to have been a type of secondary scrip flow among students that school staff had difficulty preventing. In a letter to Robert H. King from 30 March 1936 Superintendent Biery identified gambling and “sharing of income” as the two primary problems of the scrip system (“Records”). While neither staff nor students describe what the practice of sharing income entailed in written sources, it certainly seems to suggest that students exchanged money in ways other than school-sanctioned transactions. Advanced students may have accumulated enough scrip to share some with peers in lower ranks and still have money left for their own expenses. In the same way that there was a student culture beyond official clubs at many boarding schools (Lomawaima 155), scrip created a shadow economy that was largely beyond the control of staff. The more scrip students acquired, the more freedom they had to transgress their roles in the school’s market economy. Thus, it is safe to say that the implementation of scrip also inspired a new repertoire of resistance and subversion.

More than simply being examples of contrarian behavior, these comments on student behavior also speak to a deeper cultural divide that scrip could not always bridge. For instance, the fact that students apparently shared excess scrip with their peers represents a direct contradiction of the central tenets of possessive individualism. Instead of obtaining scrip exclusively for their own benefit, they used their earnings in a more communal manner, as perhaps they had learned to do growing up on reservations where there was little cash and even fewer spending opportunities. This way, students utilized scrip to ‘turn the power’ by employing one of the school’s primary tools for both assimilation and education to their advantage. At the same time, references to gambling in particular illustrate that students may not have been motivated by the culture of their communities alone. Clearly, different value systems coexisted within the capitalist framework of the scrip economy. The limited evidence of student behavior, therefore, confirms that they approached economic issues in a way that blurred the lines white officials drew between Native American ‘tradition’ and American ‘modernity.’ Although written sources offer no definitive answers as to how students viewed scrip, they neither rejected its teachings outright nor embraced them uncritically.

(L)Earning Their Place

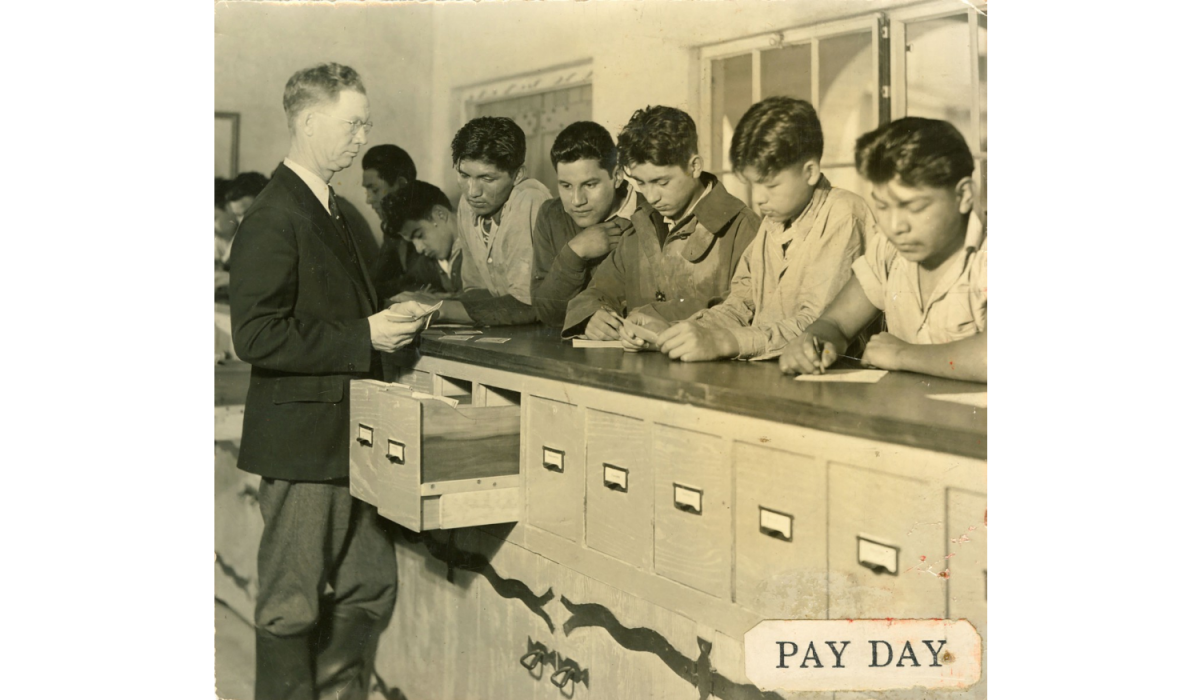

Regardless of how Sherman students used scrip beyond the supervision of school employees and the extent to which they internalized capitalist ideals, they had to adopt certain roles and behaviors to participate in school life. Indeed, Sherman staff not only recreated the American economy but did so in a way that taught students what to expect from life off the reservation. Knowing how to sew clothes, raise poultry, or repair cars was important, but students also needed to learn how those skills could make a difference in their lives. In the 1934 annual report, for example, Biery mentioned that scrip was implemented “to train for actual conditions in life concerning earning money and spending it properly” (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1934). However, scrip represented only certain conditions, illustrating that school officials expected the majority of students to apply their skills as wage laborers and spend their earnings as consumers. Additionally, classes rounded out the school’s economic training, where exclusive emphasis was placed on family budgets and private money management rather than business or investment. Moreover, in a telling example of the school’s narrow expectations of female students, budgeting classes complemented a curriculum that already focused on their future in the domestic sphere. In fact, classes in home economics for male students were optional and focused on their “contribution to the family income” (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1935). A good example of the way school staff attempted to shape students’ perspectives on work is the weekly pay day (see fig. 2). According to the 1935 yearbook, it was “looked forward to by the students with the same interest as prevails in the actual work-day world” (“Purple and Gold” 58). Although this sentiment may have been merely a projection on the part of school officials, it certainly illustrates their view of scrip as a tool for assimilation.

Figure 2. Students receive wages from senior shop instructor Frank Smith in the boys’ vocational office (“Pay Day”).

The ranking system, in particular, illustrates that scrip did not only imitate the real world but taught students how to operate within it. For one, rankings reflected a commonly used system that students were likely to encounter in non-Native work environments. More broadly, the use of a graduated pay system highlighted individual accomplishment, which is why a similar system had been part of Carlisle’s outing program several decades earlier as well (Adams 155). Students were judged exclusively by the quality of their own work and received payment accordingly, just as they would in an actual work environment. Rather than reading or hearing about the importance of hard work, students now experienced for themselves why work ethic mattered. Those who did not meet the required standards received less scrip and only had themselves to blame if they could not afford certain luxuries (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1934). Occasionally, students reminded each other of this fact in the school newspaper. In 1936, for example, the barbers noted that their peers “should not apply for barber services unless they have scrip with which to pay” (“Sherman Bulletin” 1936 4). Two years later, they struck a slightly different tone: “Any student that has not any scrip will not be serviced, so please do not hang around the shop as you will be put on extra duty” (“Sherman Bulletin” Jan. 1938 7). Failing to use money in a responsible manner was not only inconvenient but could also lead to punishment. Ultimately, the ranking system created an explicit connection between the quality of a student’s labor, their sense of responsibility, and their access to spending opportunities.

With school officials urging students to develop a sense of individual responsibility, the scrip system also redefined the significance of goods and services. Where the school had previously provided government-issued clothing and food for free, pupils now needed to work and save scrip so they could buy those necessities. Thus, it encouraged students to reflect on what they were receiving and why. This way, pupils had to learn what money could buy and how that should affect their behavior. On the one hand, it taught students that they should not expect unconditional support from authorities but learn to be self-reliant. On the other hand, students had long been told to take good care of school property, but reprimanding speeches and strongly-worded articles in the school newspaper were not as effective as administrators had hoped. The 1932 annual report, for instance, contained a lengthy account of vandalism and theft, despite an improvement in student behavior (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1932). Under the scrip system, what had been school property loaned to students now effectively became their private property. As a result, Superintendent Biery reported a “marked reduction in waste and more careful use of clothing” in his 1934 letter to Atwood (“Records” 2). Clearly, he believed that students’ use of scrip also changed their use of other material items. In the context of the scrip economy, clothes and food acquired value because students had to make decisions in relation to their incomes. Specifically, students now had to act as consumers making decisions about commodities.

Possessive Consumerism

Knowing how to work and live in a capitalist society also meant that students had to know how they were expected to put their earnings to good use. Hence, school officials drew an explicit connection between participating in the capitalist economy and being an upstanding consumer. As the 1935 yearbook put it: “Sherman students not only learn to earn, but they learn also to spend, to live within their incomes” (“Purple and Gold” 58). To this end, the scrip economy was organized, first and foremost, as a consumer society in which school staff reconstructed social relations as market relations. In essence, consumption entailed the acquisition of material items for pleasure and the wish to derive a sense of identity from those commodities (Stearns vii). Moreover, saving was increasingly perceived as a social obligation because it provided a pathway to future spending, as was also the case at Sherman. As Alison Hulme describes in her study on thrift, this shift is characteristic of a broader transition that occurred during the Great Depression (79). Increasingly, saving and careful spending became a matter of “being a wise consumer in light of collective interests” (82). Careful consumption now became an obligation for participants in the market economy because it would allow them to continue contributing to the economy. In light of these ideas, Sherman staff used scrip to show young Native Americans not only how to build a life in a capitalist society but also how their actions as individuals could benefit others.

To understand the impact of scrip on concepts of consumerism at Sherman Institute, it is critical to understand how earlier generations of students engaged in consumption. For the most part, their exposure to consumer society occurred through outside advertising and shop visits. During the early years of the Sherman Bulletin’s publication, local businesses published advertisements targeting both school employees and students. In some cases, they addressed students directly as potential consumers making informed decisions. In 1912, for instance, the Reynolds Department Store ran a simple advertisement in the school newspaper with two lists of products, adding in bold print: “For The Girls!” and “For The Boys!” (“Sherman Bulletin” 1912 4). Addressing students specifically, this advertisement is an early example of the way consumer society entered school life. Just as importantly, students had opportunities to act upon these types of messages. For one, Sherman students occasionally went on chaperoned visits to local stores, incorporating shopping into the school program as a respectable leisure activity (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1932). In addition, due to Sherman Institute’s vicinity to an urban area, pupils would sometimes leave the school without permission to spend their money on food or entertainment (Whalen, “Beyond School Walls” 282). Even though students engaged in acts of consumption well before the first scrip bills went into circulation, they did so with limited interference from school staff.

Moreover, what set the scrip system apart from earlier efforts to teach consumerism was its immersive nature. As students switched between the roles of consumers and salespeople, they simultaneously observed and performed ideas of possessive individualism. In the process, they encouraged each other to participate in consumer activity. Like true marketeers, pupils used the Sherman Bulletin to sell their products. On 18 February 1938, for instance, the school’s Dramatic Club announced a two-play double feature in the school newspaper. More than simply offering practical information, which students had always done, the authors of this announcement highlighted that audiences would get their money’s worth and encouraged their peers to “start saving those nickels and dimes” (12). Similarly, the cosmetology department advertised their wares by playing into consumer sensibilities, highlighting “reasonable prices” and promising “service with a smile” (“Sherman Bulletin” Nov. 1938 3). Whether these transactions involved scrip or dollars is unclear, but students certainly took their new roles seriously. Although one could question the extent to which they actually internalized these sentiments, it makes sense to assume that students were proud of their work and wanted others to enjoy it. Since Sherman officials had added an economic dimension to basic interactions, students were encouraged to continuously express themselves in capitalist terms. In the process, the purchasing of commodities became central to everyday life, which elevated the status of material wealth. Perhaps administrators hoped that this would change students’ perceptions of property and economic relations in general.

What makes the centrality of consumerism to Sherman Institute’s scrip economy especially important to the school’s overall agenda of economic and cultural assimilation is that consumption had deep ideological significance. By the 1930s, consumerism was increasingly considered a symbol of American identity for people of all socioeconomic backgrounds (McGovern 48-50). Moreover, the United States had used international trade to spread its economic and political values across the globe in a similar manner since the First World War (De Grazia 3-6; Sassatelli 46). As such, it is perhaps not surprising that consumerism was used to teach the ideals of capitalism in boarding schools as well. Within the scrip system, consumption served primarily to teach the central philosophy of possessive individualism, as evident, for example, in the way that the scrip economy differentiated necessities from luxuries. Food and clothes were essential items and had priority, but students should also want to work more so they could afford hair products and massages (“Superintendents’ Annual” 1934). The fact that students had to save and plan ahead to buy necessities taught a practical lesson in self-sufficiency, while the potential access to luxuries taught a desire for possessions.

School administrators, therefore, believed that if students internalized the logic of consumerism, they would not only own property but develop a sense of ownership and self-worth derived from purchases. In the process, they were expected to abandon the hybrid economies of their communities in favor of an unquestioning embrace of capitalism. Crucially, Sherman Institute’s approach in using scrip differed from that of early twentieth-century policymakers attempting to educate Indigenous communities about the value of private property. As Cahill describes, earlier generations of officials believed that “the interaction of Native people with commodities would lead miraculously to a new way of living” (47). With scrip, on the other hand, school officials created a framework in which students did not just interact with commodity items but with the market that provided access to such items. As students’ entire lives were built around the pursuit of wealth and spending, there was a tangible connection between the commodities they had access to and a specific way of life—whether they aspired to it or not. Overall, the scrip system was built on the assumption that by making consumer decisions on a daily basis, students would come to value material items and derive a sense of identity from them. This identity, while tied to other aspects of American citizenship, was rooted primarily in possessive individualism and a materialist sense of self.

Conclusion

In sum, it is evident that the scrip system provided a model of the American economy that was meant to persuade young Native Americans to embrace capitalism. Within the restrictive paradigms of the scrip economy, Sherman Institute’s students were encouraged to make specific choices that school officials hoped they would internalize and apply to their lives after graduation. Specifically, scrip differed from other efforts to teach capitalism in its participatory character and the way it incorporated economic thinking into every aspect of school life. Instead of merely describing correct behavior to students, scrip offered a direct experience to the entire student body in a way that even outing programs had not allowed. By creating a simulation of the US economy, school staff limited the possibilities for alternative behavior and presented a vision of society that left little room for noncapitalist ideas about economic life. The emphasis on consumer culture is a good example of this, as the scrip system presented a limited range of options for students to use their earnings. Even though school officials could not prevent them from using scrip to ‘turn the power,’ students had to use scrip as intended if they wanted to participate in school life. Overall, despite the fact that Sherman scrip was inevitably not an exact replica of the American macroeconomy, it served the school’s purpose of economic imperialism well enough.

In addition to teaching specific types of behavior, Sherman staff also used scrip to encourage an embrace of capitalist values pertaining to thrift and possessive individualism. With its consumerist framework, the scrip system encouraged students to redefine how they viewed themselves, their peers, and their possessions. Sherman students had seen advertisements in the school newspaper and made purchases since the school’s early days, but they had not themselves sold anything, nor had their peers treated them as consumers. Crucially, whereas scrip certainly altered the worldview of some students, they had come from environments that blended tradition and modernity in ways that defied white expectations. It is only logical to assume that Native youths continued to do so as they engaged in a new economic system at Sherman Institute. Although this makes the precise impact of scrip systems on Native American economies hard to gauge, it also illustrates the place of boarding schools in the historical trajectory from commerce during the colonial period to casinos in the twenty-first century. As Native Americans on and off reservations across the United States navigate the capitalist economy today, they follow in the footsteps of those who engaged with the US economy in the past. In the end, although there is more work to be done on the use of currency by Indigenous communities in the United States, scrip illustrates that their participation in the capitalist dollar economy has historically been neither straightforward nor self-evident.

Works Cited

Archival and Other Primary Sources

“Charles E. Larsen Chemawa Indian School Collection, 1853-1953.” Box 2, Folder 9, Willamette U Archives and Special Collections, Salem, OR. Archives West, libmedia.willamette.edu/cview/archives.html#!doc:page:manuscripts/5837.

Meriam, Lewis, et al. “The Problem of Indian Administration.” Johns Hopkins P, 1928. Native American Rights Fund, www.narf.org/nill/documents/merriam/b_meriam_letter.pdf.

“Pay Day.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection, Series 15, Box 113, Folder 1.

“Purple and Gold.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection, Series 16, Box 180.

“Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: Records of Sherman Institute.” RG 75, National Archives and Records Administration Pacific Region, Riverside, CA. National Archives, www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/075.html.

“Sherman Bulletin, January 3, 1912.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, September 21, 1928.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, December 1, 1933.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, January 5, 1934.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, September 21, 1934.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, October 2, 1936.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, January 21, 1938.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, February 4, 1938.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, April 1, 1938.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

“Sherman Bulletin, November 18, 1938.” Sherman Indian Museum Collection.

Sherman Indian Museum Collection. Sherman Indian High School, Riverside, CA. Calisphere, calisphere.org/collections/27124/.

“Superintendents’ Annual Narrative and Statistical Reports, 1910-1935.” RG 75, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. National Archives Catalog, catalog.archives.gov/id/156005969, catalog.archives.gov/id/156004799.

United States, Department of Commerce. Survey of Current Business, November 1933. US Dept. of Commerce, 1933, apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/1933/1133cont.pdf.

Secondary Sources

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. UP of Kansas, 1995.

Bahr, Diane Meyers. The Students of Sherman Indian School: Education and Native Identity Since 1892. U of Oklahoma P, 2014.

Bloom, John. To Show What an Indian Can Do: Sports at Native American Boarding Schools. U of Minnesota P, 2000.

Cahill, Cathleen D. Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869-1933. U of North Carolina P, 2011.

Coleman, Michael C. American Indian Children at School, 1850-1930. UP of Mississippi, 1993.

De Grazia, Victoria. Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through Twentieth-Century Europe. Belknap P, 2005.

Fear-Segal, Jacqueline. White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation. U of Nebraska P, 2007.

Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, and Susan Rose, editors. Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations. U of Nebraska P, 2016.

Gettler, Brian. Colonialism’s Currency: Money, State, and First Nations in Canada, 1820-1950. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2020.

Gram, John R. Education at the Edge of Empire: Negotiating Pueblo Identity in New Mexico’s Indian Boarding Schools. U of Washington P, 2015.

Harmon, Alexandra, et al. “Interwoven Economic Histories: American Indians in a Capitalist America.” Journal of American History, vol. 98, no. 3, 2011, pp. 698-722.

Hosmer, Brian, and Colleen O’Neill, editors. Native Pathways: American Indian Culture and Economic Development in the Twentieth Century. UP of Colorado, 2004.

Hulme, Alison. A Brief History of Thrift. Manchester UP, 2019.

Jacobs, Margaret D. White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880-1940. U of Nebraska P, 2009.

Keller, Jean A. Empty Beds: Student Health at Sherman Institute, 1902-1922. Michigan State UP, 2002.

Littlefield, Alice. “Learning to Labor: Native American Education in the United States, 1880-1930.” The Political Economy of North American Indians, edited by John H. Moore, U of Oklahoma P, 1993, pp. 43-59.

Littlefield, Alice, and Martha Knack, editors. Native Americans and Wage Labor: Ethnohistorical Perspectives. U of Oklahoma P, 1996.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of the Chilocco Indian School. UP of Nebraska, 1994.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina, and Teresa McCarty. “To Remain an Indian”: Lessons in Democracy from a Century of Native American Education. Teachers College P, 2006.

Macpherson, C. B. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Oxford UP, 1962.

McGovern, Charles. “Consumption and Citizenship in the United States, 1900-1940.” Getting and Spending: European and American Consumer Societies in the Twentieth Century, edited by Susan Strasser et al., Cambridge UP, 1998, pp. 37-58.

O’Neill, Colleen. “Rethinking Modernity and the Discourse of Development in American Indian History.” Introduction. Hosmer and O’Neill, pp. 1-24.

Parkhurst, Melissa. To Win the Indian Heart: Music at Chemawa Indian School. Oregon State UP, 2014.

Reyhner, Jon, and Jeanne Eder. American Indian Education: A History. U of Oklahoma P, 2004.

Sakiestewa Gilbert, Matthew. Education Beyond the Mesas: Hopi Students at Sherman Institute, 1902-1929. UP of Nebraska, 2010.

Sassatelli, Roberta. Consumer Culture: History, Theory and Politics. SAGE, 2007.

Stearns, Peter N. Consumerism in World History: The Global Transformation of Desire. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006.

Trafzer, Clifford E., Jean A. Keller, et al., editors. Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. UP of Nebraska, 2006.

Trafzer, Clifford E., Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, et al., editors. The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue: Voices and Images from Sherman Institute. Oregon State UP, 2012.

Trafzer, Clifford E., and Leleua Loupe. “From Perris Indian School to Sherman Institute.” Trafzer, Sakiestewa Gilbert, et al., pp. 19-34.

Trennert, Robert A. “From Carlisle to Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of the Indian Outing System, 1878-1930.” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 52, no. 3, 1983, pp. 271-75.

Vuckovic, Myriam. Voices from Haskell: Indian Students Between Two Worlds. UP of Kansas, 2008.

Whalen, Kevin. “Beyond School Walls: Indigenous Mobility at Sherman Institute.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 3, 2018, pp. 275-97.

---. “Finding the Balance: Student Voices and Cultural Loss at Sherman Institute.” American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 58, no. 1, 2014, pp. 124-44.

---. Native Students at Work: American Indian Labor and Sherman Institute’s Outing Program, 1900-1945. U of Washington P, 2016.

Williams, Carol, editor. Indigenous Women and Work: From Labor to Activism. U of Illinois P, 2012.