Abstract: Whether it allowed for women’s employment, mass production and consumption of ready-to-wear fashion, encouraged their creative individuality through sewing patterns, accompanied them into the public sphere, or triggered their sociopolitical emancipation in protest marches: the sewing machine played a decisive part in women’s experience of American modernity, mass culture, class, and (feminist) emancipation. Within symbiotically related experiences of modernity and mass culture, this paper reads the sewing machine as feminine modernity’s very ‘motor’ that allowed for a distinctively feminine experience of modernity in New York City. It took up a complex middling position that oscillated along the public versus private sphere continuum, (class-biased) roles of producer and consumer, and, in a bidirectional movement, at once expanded and enforced women’s spatial and socioeconomic boundaries. Emanating from theoretical frameworks of separate spheres and modernity in a gender context, I analyze this cultural artifact’s representation. By examining contemporary sewing machines’ designs and patterns of use as implied by trade cards and other forms of advertisement that targeted women of varying class, economic, and family status backgrounds in the modern era, the central role this machine played can come to the forefront.

In order to account for the complexities and contradictions of feminine modernity, the present text delineates and analyzes the multilayered connections between sewing machines, femininity, and modernity in New York City by arguing that the sewing machine allowed for a distinctively feminine experience of modernity. Following Ben Singer’s enumeration of the “six facets of modernity,” I demonstrate how the sewing machine allowed women within New York City to experience not only “[m]odernization” and “[r]ationality,” but also “[m]obility and [c]irculation,” “[i]ndividualism,” as well as “[s]ensory [c]omplexity and [i]ntensity” and “[c]ultural [d]iscontinuity” (20-35). In addition to referring to these facets as significantly ‘feminine,’ New York City is read as a metonymy of this specifically ‘feminine’ experience of modernity in the United States as a whole.

The combination of woman and machine played out across class contexts and offered varying, yet symbiotically related experiences of modernity and mass culture. Oscillating along a public versus private sphere continuum, these experiences at once widened and affirmed the boundaries set by the separate spheres ideology. The sewing machine took up a middling position that enabled a particular experience of modernity for women in their emerging roles as both producers and consumers of mass-produced fashion. In order to avoid too normative dichotomies of private and public sphere, producer and consumer, or working and middle class, the paper concentrates on the concatenation of various roles that the sewing machine created for women in New York City’s modern era. To bring out these nuances, I employ multifaceted and polysemic readings of the semiotics of the sewing machine. Singer’s definition suggests that American modernity was characterized by a “[c]ultural [d]iscontinuity” (24). At the center of this analysis will be the semiotic recoding of signs and their respective significations both within social life (e.g., women’s changing status within society) and also within the realm of cultural artifacts such as the sewing machine.

In line with Hartmut Rosa’s idea of the “[a]cceleration of [s]ocial [c]hange” (“Social” 82-85), particularly during the first “wave of acceleration” (78) that lasted from 1880 until the late 1920s, I argue that the sewing machine, as a ‘motor’ of sociopolitical movement, allowed women to challenge the separate-spheres ideology. At this time, women joined the workforce in factories and labor unions’ protest marches that informed gender relations. Still, the sewing machine refuses to eliminate this barrier completely; in enabling women to easily sew their own clothes at home whether out of necessity, for charity, or leisure, the sewing machine also reinforced women’s domestic roles.

This opposition of the sewing machine being either a ‘motor’ for progress and development or a tool that secures a gendered status quo of social stagnation takes up a decisive controversy within the field of modernity and temporality studies. Unlike Singer’s definition intimates, the modern era is often misread as an era of progress, change, and acceleration. Presenting the sewing machine as a middling instrument that negotiates between tradition and progress, I therefore also delineate tendencies of deceleration instead of solely acceleration,1 as ‘motors’ and ‘machines’ are also capable of slowing down and halting altogether. Singer’s definition of modernity remains useful since it enumerates certain parameters for a broad analysis of the sewing machine as women’s ‘motor’ of a distinctively modern experience within a US American urban context.

Emanating from theoretical frameworks of separate spheres and modernity in a gender context, the sewing machine and its inherent audiovisual sensory experience and motion can be understood as modernity’s very ‘machine’ of class-biased mass production and consumption. The use of the word ‘machine’ thereby also significantly challenges essentialist notions of modern machinery as ‘masculine,’ let alone as purveyors of a ‘masculine’ experience of modernity. Instead, my analysis recognizes the ‘feminine’ in modernity’s very machine-ness. While taking up a complex intermediary position between private and public sphere, the sewing machine also constructed feminine identity and experience in modernity. In this context, the analysis of noncommercial sewing implies a rejection of mass-produced uniformity through women’s individual expression in modernity’s urban crowd.

Theoretical Frameworks in the Porous Fabric of Modernity

In order to analyze the complex intersections between women and the modern experience as evident in the gendered context of the sewing machine, two analytical frameworks are employed: the separate-spheres ideology and the (mis-)association of modernity with masculinity. These are set against the metaphor of woman as machine. A commonly held misconception is the “equation of masculinity with modernity and of femininity with tradition,” writes Rita Felski in her introduction to The Gender of Modernity (2). She laments that, more often than not, modernity’s “key symbols [...]—the public sphere, the man of the crowd, the stranger, the dandy, the flâneur” were connoted as male and public, thus relegating women, with their ‘inscribed’ “feminine values of intimacy and authenticity,” to the private, domestic, and non-modern sphere (16-17). There, they remained “untouched by the alienation and fragmentation of modern life,” so that “the modern is predicated on [...] the erasure of feminine agency and desire” (17).2 Through this criticism, women’s experience of modernity, both in the private and the public sphere,3 can be made visible. As Felski continues, women could only interfere in this equation of modernity with masculinity if they “[took] on the attributes that had been traditionally classified as masculine” (19). Thus, the commonly male-connoted machine-ness of the sewing machine provided women with an entrance to this equation and the discourse of modernity.

The sewing machine allowed for a novel “metaphorical linking of women with technology and mass production” (Felski 20), which constructed women’s modern social role as increasingly informed by the machine. Taking up modernity’s discourse of fragmentation and destabilization of social norms (also in a way of semiotic recoding), the “image of the machine-woman” not only “denaturalize[d],” but even “demystif[ied] the myth of femininity” (20) as Felski convincingly argues. It thus provided an anti-essentialist view of femininity based on gender identity as a complex social construct.

To associate the modern experience only with the public sphere, however, would also be a misconception. The sewing machine proves an apt example here in that it provided women with employment both in the factory and the tenement sweatshop. This blurs the lines between public and private regarding the gendered division of labor, so that, as Barbara L. Marshall elucidates, “[t]he public-private division set up as the expression of the gendered division of labour must necessarily fall” (50). Concluding her introduction, Felski asks: “[W]hat if feminine phenomena, often seen as having a secondary or marginal status, were given a central importance in the analysis of the culture of modernity?” (10). In utilizing the sewing machine, a specifically feminine experience of modernity is highlighted. Like machines that accelerate and decelerate, this experience is mediated between women’s emancipatory progress and social stagnation.

The Sewing Machine as Mass-Cultural and Modern Artifact

Set between private and public sphere, production and consumption, as well as between dichotomies of class and gender, the sewing machine itself takes on multiple meanings that deserve attention. Applying Felski’s feminist approach (“Modernity and Feminism” 11-34), the semiotics of the sewing machine exhibit their own “sign-laden nature” and “intertextual relationships” (28-29). The following chapters will then highlight the particularly polysemic nature of the sewing machine and its gendered context in women’s experience of modernity.

A mass product itself, the factory sewing machine displayed the sensory experience of modernity in its inherent focus on motion, but also in its mass manufacture in standardized work processes that provided both seamstresses and female consumers with a distinctive experience of the era. As a marker of a modern machine aesthetic of speed, acceleration, efficiency, rationality, standardization, seriality, urbanity, as well as anonymity due to its heightened output of (anonymously produced) mass products for the mass market, the sewing machine became modernity’s very ‘machine’ of mass production and consumption—if not even its motor.

According to Singer, rationality influenced modernity as “an era in which logical systems-building informs most avenues of human endeavor,” while “emphasiz[ing] an intellectual orientation toward deliberate calculation of efficient means for achieving concrete, clearly delimited ends” (22). In “capitalist modernity,” this implied “task specialization and chain of decision-making authority” to achieve utmost efficiency and productivity, also emphasizing time and speed (23)—all of which becomes apparent in the cultural artifact of the sewing machine. After Elias Howe’s 1846 invention of the sewing machine had started its mechanization, its electrification in the 1910s “permitted the sewing of 800 to 900 stitches a minute” (Helfgott 38), conforming to modern imperatives of speed, efficiency, and productivity.

In his history of the sewing machine, David A. Hounshell delineates the emergence of Singer sewing machines as a mass product. This emergence was facilitated primarily through outsourcing4 its manufacturing of parts from the actual assembly in 1883 and resulted in a new annual output of 600,000 machines (116). Indeed, the production process adopted the language of modernity that same year when “[a]ccuracy, system, and efficiency had become important watchwords” (118). “[U]niformity” and “productivity,” measurable in the “quantity of output,” the “systematiz[ation]” of labor, “strict procedures,” “bureaucratiz[ation],” “task force” creation, and the “absolute interchangeability of machine parts” (119-20, 122) were also taken up into the company’s new vocabulary. This notion expresses the idea of modernity as outlined by Singer (20-35).

New York City’s garment factories at the turn of the twentieth century can be examined as modern spaces. Set in a central location, they “thriv[ed]” on urbanity and “economic advantages of congestion” (Green 216, 226). New York City’s supremacy in women’s wear production is owed largely to four determinants: its strategic location that created a “geography of garment making” (219), the urbanization of sewing, the high concentration of an (immigrant) workforce that was prepared to labor for low wages, as well as New York City’s growing bona fides as a major shopping metropolis. The importance of New York City to the garment industry becomes even more central in the figures that Nancy L. Green provides, showing that while in 1899 “65 percent of the total value of American-made women’s wear” had been produced in New York City, this share amounted to “78 percent in 1925” (214). Next to securing the city’s nationwide dominance in the manufacturing of apparel (Currid 21), the “clustering of support industries” (Green 216) also addressed modern-era imperatives of density and efficiency that were perfectly aligned with the modern urban experience.

The story of New York City as a story of garment production is also characterized by urbanization. During the 1920s, the city’s garment manufacturing and shopping districts moved northwards from the Lower East Side to the Garment District in Midtown Manhattan. This relocation was aided by the arrival of large-scale department stores and shopping corridors along 6th Avenue, as well as by the opening of Penn Station in 1910 and the resulting influx of potential consumers (Green 217).

Within factories themselves, repetition, if not even serialization, informed the industrial production mode (Brasch and Mayer 5). An anonymous mass of workers produced garments en masse in synchronized work processes. This modern production mode prefigured both the Fordist assembly line introduced in 1913 and Taylorist characteristics of the optimization of work processes. Garment factories availed themselves of “section work” with its division of labor “into a number of operations, the work being passed from operator to operator by hand” (Helfgott 37).5

In the 1920s, aided by increased wealth and leisure time, fashion became a “consumer force” that demanded for constantly new and faster fashion output, resulting in the necessity for higher production rates (Helfgott 57). The years between 1914 and 1919 alone saw a steep sales increase of factory-made dresses6 that diametrically opposed plummeting cotton sales figures (Gordon 14). Thus, in steadily replacing tailor-made fashion, mass-produced ready-to-wear fashion exhibited acceleration, rationality, standardization, and anonymity. Ready-to-wear fashion enabled quick reactions to the ‘speed’ of fashion, yet also resulted in mass-advertised uniformity of appearance in the urban crowd. Fashion and fashion cycles thereby demonstrate a serial nature of repetition that is open to variation (Kelleter 22), borrowing keywords from modern mass culture and modernist art forms. A conflict became apparent, however, when mass-producing factories were faced with fashion’s demand for seasonal style changes (Helfgott 40). These factories quickly found that they were not flexible enough, which validates Frank Kelleter’s notion of ‘variation’ within serial production (22).

Literally ‘working like machines,’ wage laborers themselves were steered by modern discourses of rationality, as outlined by Margaret M. Chin. In the interwar years, the task-based and piecework payment system, i.e. payment according to the “produc[tion] [of] a certain number of pieces in a set amount of time” (8) was replaced by a time-based payment system (12). This symbolizes modernity’s demand for time-efficiency and mass production irrespective of quality or individuality. As Louise C. Odencrantz points out, “[f]or workers in New York City the emphasis was on speed and completing tasks for mass marketing, not quality and one-of-a-kind pieces” (qtd. in Chin 10). Additionally, in the context of utmost efficiency of production time and price, as well as electrification, time-based payment systems implied decreasing wages for the laborer.

Regarding the work process itself, standardization led to alienation. As Peter Barry illustrates, “the worker is ‘de-skilled’ and made to perform fragmented, repetitive tasks in a sequence of whose nature and purpose he or she has no overall grasp” (151). In a sense of reification, the worker becomes the machine. This machinelike perception of modernity is enhanced by the latter’s description in terms of audiovisual sensory experience and complexity, as seen in Ben Singer’s or Walter Benjamin’s texts. Speaking of “modernity-as-stimulus,” Singer explains that the modern “metropolis subjected the individual to a barrage of powerful impressions, shocks, and jolts,” resulting in a “markedly quicker, more chaotic, fragmented, and disorienting” (subjective) experience of the city than before (34-35). Likewise, Benjamin’s use of the term ‘shock’ referred to a particularly modern aesthetic perception and “sensory upheavals” in the modern metropolis (Singer 130).

Heinz Ickstadt’s definition of modernism refers to “practices of literature and art which [...] break with conventions” or “reinvent traditions” to “express the experience of modernity” (218, my translation). Following this definition, the procedure of sewing itself exposes modern(ist) traits: The machine’s steadily and audibly moving needle expresses consistency of movement and acceleration in audiovisual terms. The sewing machine thus functioned as a constant reminder of the seamstresses’ socioeconomic position in the modern machine age’s hub of efficiency, acceleration, and alienation. Owing to the steady tact of production, the needle’s persistent movement, and the machine’s monotonous rattle, the same machine became a symbolic ‘motor’ for the more affluent woman’s consumer culture of fashion.

How One Half Wears What the Other Half Sews: Mass Production and Consumption of Ready-to-Wear Fashion

Class interdependency characterized the ready-to-wear fashion industry’s emergence in New York City. Middle- and upper-class women’s experience of modernity, with its introduction of the department store and the concomitant advertisement and consumption of mass-produced goods, relied heavily upon working-class (immigrant) women’s wage labor in factories or sweatshops (Bender 19).7 Through mass production, working-class women working mainly for their own subsistence enabled middle- and upper-class women’s mass consumption. Departing from a too rigid and socioeconomically stratified consumer-producer divide, this chapter addresses working-class women’s accelerated ‘motion,’ here implying (immigrant) working women’s social mobility and political movement as driven by the sewing machine’s motor. Following, I address middle-class women’s mass consumption of fabricated garment and its meaning for their modern experience. The examples provided further highlight how the sewing machine allowed for the constant (re-)coding of women’s experiences of modernity within New York City in varied, if not even polysemic directions.

Moved by Machines I: The Woman in the Modern Sweatshop as a Danger to US Cultural Values

The sewing machine can be read as a motor of women’s upward social mobility and a path to the public sphere in offering them employment, participation in the public sphere, and the experience of wage earning, though more for subsistence than for financial independence. At the same time, the machine also subjugated women to a regime of rational, monotonous, fast, and often dangerous work processes, thus taking a middling position between social mobility and stagnation.8 Working-class women’s sensory experience of modernity’s discourse of accelerated and always more efficient work processes was particularly characterized by noise, heat, and air pollution, if not even fire hazards. Tenement sweatshops,9 with their place of production being situated between private and public sphere, offered similarly abhorrent working conditions that often involved child labor within New York City’s immigrant residential areas.

Employing a predominantly female immigrant workforce in garment production within (immigrant) tenement buildings, the sweatshop was deemed “an unnatural and foreign workplace” (Bender and Greenwald 5-6). Middle-class reformers and inspectors, in particular, applying modernity’s language of rationality, perceived sweatshops “as primitive capitalism easily fixed by economic progress, efficiency, and government regulations” (6, my emphasis). Thus, the early twentieth century saw the formation of unions and the resultant decline of sweatshops (Helfgott 50-51).10 As Bender remarks, another “goal of [the] antisweatshop movement” was the assertion of control over and “restriction of women’s paid labor” (28). Reformers and predominantly male workers deemed women’s sweatshop labor a “moral danger” detrimental to the “social and cultural ideal [...] of the male breadwinner” (29, 32). To revisit Felski’s initial argument of a semiotic recoding of women’s social roles, one may argue that reformers feared the evolving ‘machine-woman’ and the concomitant “denaturaliz[ation]” and “demystif[ication] [of] the myth of femininity” (20).

In the context of early-twentieth-century immigration, progressivists viewed the “sexual division of labor” as “an easily identifiable Victorian-American social standard” for immigrants and thus as a pillar of US cultural assimilation (Bender 29). Many Jewish immigrants, in particular, embraced the idea of US cultural assimilation through a separation of home and workplace by viewing a working married woman as an indicator of poverty and “men’s breadwinning” as “a sign of assimilation and success” (30). Rather than indicating their independence in the ‘free nation,’ immigrant women’s sweatshop labor was thus stigmatized as a “symbol of the moral, physical, and racial perils of sweated work” (31). Ironically, it was a male “garment worker and unionist,” Abraham Rosenberg, who led a strike that partially defeated the sweatshop in 1910 (Bender and Greenwald 10).

Moved by Machines II: The Sewing Machine and Women’s Political Activism

“175 Die in Blazing Fire Trap; Nearly All Victims Women” read the headline of the San Antonio Light Newspaper on March 26, 1911, one day after the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City (“100 Years After”). The article continues to describe that “some of [the dead are] pitifully young to take up the burden of wage earners and some of them old women that an unkind fate kept in the battle for daily bread when their years should have won them a peaceful close of life” before it turns to blaming the “tragedy” on the neglect of workplace safety which was only introduced after the event (“100 Years After”).

Whereas this article hints at a victimization of working women in the modern era, women were at the same time perceived as “increasingly dangerous”—particularly when they appeared “in organized groups of the suffrage or strike crowds but also in generalized groups such as shoppers, working girls, or spinsters” (Parsons 44). Young immigrant working women organized for unionization and strikes within the “union stronghold” New York (Bender and Greenwald 9). Applying the language of modernity, the sewing machine thus enabled a movement which provided both working-class women and middle-class New Woman reformers with yet another possibility for social upward mobility and the establishment of political agency in modernity’s public sphere. At the same time, the boundary between lower-class garment workers and middle-class reform activists was not always clear-cut. For example, in 1904 both middle- and working-class women joined forces to form the Women’s Trade Union League in New York City. This was done “to oppose child labor and lobby for protectionist legislation” as well as to “[investigate] conditions in sweatshops and [organize] striking workers” (Adams et al. 7). The ‘Uprising of the 20,000,’ “the largest strike by women in American history” (Greenwald 79), had ironically already called for safety improvements in 1909, yet had been thwarted. The fire renewed women’s political action in light of “deteriorating labor conditions” and the “highly publicized and violent labor uprisings in the 1910s” (Guglielmo 191). As a result, during the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union11 strike in 1913, 4,000 female garment workers participated in protest marches against gender-related unequal payment (185).

Moved by Machines III: Women’s Mass Consumption in the Public Sphere

The experiences of “urbanization [...] [,] consumerism,” growing “[i]ndividualism,” and “[s]ensory [c]omplexity and [i]ntensity” are key markers of a distinctively feminine experience of modernity (Singer 21, 30, 34). Closely entangling modernization with urbanization, the city becomes “a demonic femme fatale whose seductive cruelty exemplifies the delights and horrors of urban life” (Felski 75). Previous scholarship has too often linked “seduct[ion]” and consumerism to femininity. As Felski argues, “the category of consumption situated femininity at the heart of the modern in a way that the discourse of production and rationalization [...] did not” (61). While warning that consumption, contrary to production, should not be “devalue[d] [...] as [...] passive” (63), Felski also asserts that women’s “consumption cut across the private/public distinction that was frequently evoked to assign women to a premodern sphere” (61). For instance, by shopping in the city’s newly emerging public-sphere department stores and shopping arcades, the ‘woman-as-consumer’ was able to transgress spatial boundaries.

Making a class bias more evident, the “[i]ndividual’s ownership of own labor power” and “self-determin[ation]” (Singer 31), and thus the perception of consumption as liberation facilitated by growing financial and spatial independence, only applied to a middle-class clientele. The ‘sign’ of the department store presented or even signified for the middle- and upper-class woman what the factory was for the lower-class woman: urban public spaces of living out their experience of modernity within respective class boundaries. In the public sphere, men predominantly managed the stores and their marketing, while “consumer culture,” even in the private sphere (e.g., through fashion magazines), “subject[ed] women to norms of eroticized femininity that encouraged constant practices of self-surveillance” (Felski 90). These practices reinforced the impulse to buy and turned shopping into a publicly performed domestic ‘duty.’ This situating of women between independence from and subjugation to traditional gender norms across separate spheres deserves further attention.

Home Sewing and the Woman in the Crowd versus the Woman in the House

The following cultural analysis unravels the home sewing machine’s12 complexities and ambiguities that positioned women between traditional feminine gender notions of domestic dependence and motherhood and ideas of emancipation, employment, and independent spatial movement. Contemporary sewing machines’ designs and patterns as well as trade cards and other forms of advertisement that targeted women of varying class, economic, and family status backgrounds in the modern era serve to provide evidence for the public versus private sphere continuum.

As Singer outlines, modernity saw “[women’s] expansion of heterosocial public circulation and interaction, [...] the decline of the large extended family,” but also “the separation of workplace and household as well as the shifting of the primary unit of production from the extended family to the factory” (Singer 21; cf. Gordon 14). A growing female workforce significantly aided this shift: Between 1870 and 1930, the female workforce increased from fourteen per cent (1870) to over twenty per cent (1910) and then to twenty-two per cent (1930) (Norton and Alexander qtd. in Gordon 14). Eventually, faced with the 1920s’ decline in demand for sewing-related products due to the aforementioned shifting gender notions and the mass-cultural availability of cheap ready-to-wear clothing, marketing campaigns of sewing machine manufacturers and sewing pattern magazines targeted the True Woman and the New Woman at once, thereby commodifying (performances of) gender.

Mother’s Helper: The Sewing Machine, Domesticity, and Motherhood

Decades before Betty Friedan criticized the medially constructed placement of women in the home in The Feminine Mystique, the sewing industry employed the symbol of the sewing machine in order to increase its sales figures. This was done by ‘selling’ the idea of domesticity and tradition as an essentially feminine one, thereby counteracting what Singer calls the fear of “loss of cultural moorings in modern life” (25). According to Felski, the leitmotif of nostalgia, such as “yearning for the feminine as emblematic of a nonalienated, nonfragmented identity,” characterizes modernity (37). Women’s elimination from the public discourse of modernity becomes evident in “sociology’s nostalgic [i.e. non-, or at least premodern] view of women” (55). This view positions women in “the sphere of Gemeinschaft, or community, anchored within the home and a network of intimate and familial relationships” which is “contrasted with the artificial and mechanical world of Gesellschaft” that is consequently connoted as male (55). Already the name of the first home sewing machine, “New Family,” which was introduced by Singer in 1865, seems to market a tripartite ‘deal’ of “[s]ewing machines, motherhood and domesticity” to women (Douglas 22).

Evoking and commodifying domestic ‘virtues’ of “maternal responsibility, financial caution, feminine attractiveness, social connections, and household respectability,” as Sarah A. Gordon argues, “[s]ewing was [...] a distillation of American ideas about what women should do with their time and for their families” (27). As Marshall states, “[t]he ‘modern’ bourgeois family emerged not with some abstract separation of household and work-place, but with the entrenchment of motherhood as a vocation for white, middle class women” (55, my emphasis). Still, Marshall warns not to de-emphasize or belittle women’s domestic role in hindsight, as women actually “played a vital role in [the public spheres of] industrializing economies” and “family survival,” which was “reinforced” by “[a] growing social reform movement” (54-55).

The notion of mothers’ life improvement through the sewing machine is especially reflected in advertisements’ addressing of sewing clothes for one’s children or, exhibiting progressivist ideals, of proper child rearing. Quoting the Industrial Commission, Green remarks that manufacturers “argued that women’s place was in the home, and that forcing them out to the shop would only cause hardship,” as they were “obliged to leave [their] children alone all day” and thereby “virtually abandoned them” (221).13 In the figure “Mother’s Helper,” the text therefore promotes ideal motherhood in the ‘busy’ modern era by emphasizing the machine’s efficient and time-saving benefits as “[m]other’s [h]elper” which assists sewing women in their simultaneous motherly duties with a “[h]andy [e]xtension [l]eaf.” Encircled by the message that promises the obvious solution for combining work and family duties, both mother and toddler appear content as each benefits from this practical machine (“Mother’s Helper”).

Even if women contributed to the nation’s economy through their increasing participation in the workforce, marketing strategies still sold the sewing machine as a savior of “happy homes” and “leisure hour[s]”14 in the contexts of gender roles’ upheaval and new time shortages (Gordon 6). Thus, along with implying that sewing machines were able to “sooth family tensions, reduce women’s drudgery, and save money and time” (6), the pairing of modernity’s acceleration and efficiency discourse with ideal motherhood suggested women’s belonging to what Felski called the non- or “premodern” private sphere (55). This ‘premodern’ notion of women’s domestic and financial dependence is also addressed in trade cards that depict brides who receive sewing machines as wedding gift, paid for by their ‘breadwinner’ husbands, who thus ensure that women complete their domestic ‘duties.’15

A note of paternalism accompanies women’s home sewing in modernity, as evidenced by The Philosophy of Housekeeping, a household manual from 1867. This manual praises the sewing machine as a “masculine invention” (connoted with publicly-manufactured ‘male’ technology) that “has come to the aid of feminine patience and industry” (Lyman 486-87) in the domestic sphere. Still, Gordon remarks that the promotion of sewing machines’ cost efficiency implied women’s control over the household budget, appealing to the True Woman’s “thrift as virtue” (26).16

Designing the Domestication of the Machine and the Mechanization of Mobility

The introduction of the public-sphere machine into private-sphere domesticity enabled women’s spatial movement into the public sphere. It led to the machine’s “encroach[ment]” into and “commodification” of “the sanctity of the private and domestic realm” (Felski 61-62). The sewing machine became a literal household item, pointing to a gender bias: “[D]esigned and manufactured by men” in the public sphere, the home sewing machine was “consumed and operated by women” in the private sphere (Zhang 178). Li Zhang points out several transitions: from the “factory” to the “family,” “from industrial coldness” to “aesthetic attractiveness,” from “large to miniature,” from “open structure to concealment,” from workbench to “furniture,” “from complexity to easy-to-use, from public sphere to the private and individual; in short, from masculinity to [...] femininity” (178). However, this domestication and ‘feminization’ of the machine, evident in its design and strategic focus on domestic purposes, exhibited a dual function in also enabling women’s movement into public-sphere employment, socialization, and urbanity.

The aforementioned domestic practicability and efficiency became evident in the home sewing machine’s design. With a visibly ‘feminized’ design, the man-made machine’s “material and structure were marked with obviously muscular features, while the decoration on its surface and its curved shape were typically feminine” (Zhang 178). Zhang elaborates that the use of wood and “intense feminine gamosepalous patterns with bold golden color,” but also the “small size” and weight, as well as “soft curve[s]” hinted at the machine being “exclusively designed for female consumers” (179). Often advertised in contemporary trade cards, its furniture-like design facilitated the machine’s seamless integration into domestic parlors—where, depending on size, it could be used as a dining table or be stowed away. As Douglas notes in her analysis of the sewing machine’s domestic design, this hiding of the machine from view “emulat[ed] upper class” living room styles (26). The sewing machine thus enabled the socioeconomically upward stylization of the parlor.

Further, the machine’s small size and portability permitted women’s spatial mobility by entering public-sphere socialization, as later advertisements emphasize, while simultaneously limiting this spatial and temporal movement to a friend’s house or weekend and vacation trips. This new addressing of working women becomes even clearer in an advertisement that describes the sewing machine’s size as “no larger than a typewriter” while depicting a sewing woman, reminiscent of women’s advancement into white-collar jobs, at a desk. Nonetheless, as the accompanying text suggests, the home sewing machine was just like a typewriter, thus merely a domestic simulation of a public-sphere office experience. Additionally, while advertisements depicted secretary desks as an “‘office space’ for the woman of the house,” Douglas objects to the idea that this “woman’s business” was truly domestic (26).

“A New Home or a Divorce”: Home Sewing and New Women

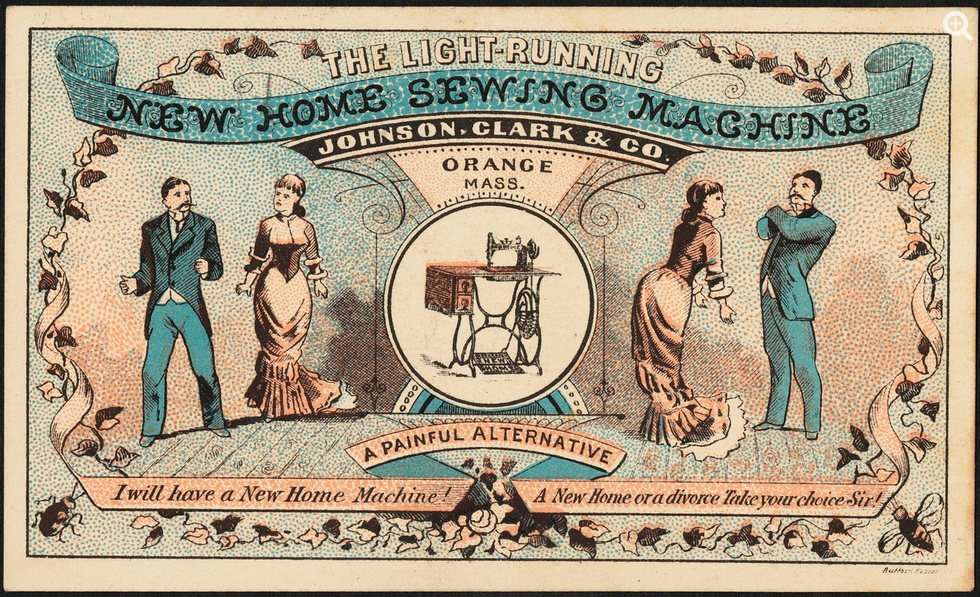

The woman in the Johnson & Clark trade card presents her husband with “a painful alternative,” as suggested by the text: “I will have a New Home Machine! A New Home or a divorce[.] Take your choice, Sir!”. Visually, the object of the present woman’s desire portrays two representations of a couple that can be read from left to right. The woman’s unsatisfied facial expression on the left-hand side is contrasted with a drawing that presents the viewer with her solution for this unsatisfaction. Her body leans toward her husband in order to underline her argument. The viewer does not find out whether her pleas were heard. In a manner of appropriating a man-produced machine, the sewing, mechanized New Woman viewed the “sewing machine as her political and practical ally” (Douglas 21). Thus, the New Woman semiotically recoded the same domestically connoted machine that offers a “[h]andy [e]xtension [l]eaf” (“Mother’s Helper”) into a machine that extends its hand to her emancipation from male dominance. Conversely, with the advertisement of an explicitly “Light-Running New Home Sewing Machine,” the Massachusetts-based company seems to suggest to the implied reader that purchasing this machine will have a positive effect on marital life by facilitating its ‘running.’

“The Light-Running New Home Sewing Machine”

In a New York Times editorial, dating from November 18, 1875, the editorialist describes a sewing machine advertisement in which the sewing machine “usurp[s]” the “husband’s place in the family”:

The father is absent, having plainly been driven away by the noise of the sewing-machine, [...]. Plate number three shows the husband on his death-bed. The machine has evidently finished him at last, and his wife is exultingly remarking to herself that her machine is ‘exempt from execution and not perishable.’ The children are crying in a most edifying manner, but there is a sweet smile on the face of the dying man, which betrays his consciousness that he is going where sewing-machines never rattle, and needles never break. (Douglas 21)

As illustrated vividly in this editorial, the machine and its upheaval of traditional gender hierarchies of power had traumatic effects on the individual.17 In the commentary in a 1909 issue of The Independent, author Susanne Wilcox disapproves of this new ambiguity and the demise of the “plain housewife”:

The plain housewife is rapidly disappearing, and is being superseded by a conspicuous minority of restless, ambitious, half-educated, hobby-riding women on the one hand, and by the submerged majority of sober, duty-loving women on the other, who are nevertheless secretly dissatisfied with the role of mere housewife. (qtd. in Adams et al. 9)

It becomes clear from this commentary that modernity’s rupture with traditional gender hierarchies left the individual with a new uncertainty regarding gender roles.

Fabricating Freedom: The Role of Home Sewing in Preparing the Woman of the Crowd

Concerning employment, home sewing prepared women for their participation in the workforce across various class backgrounds. Next to tenement shops or factories, sewing working-class women were employed as seamstresses for affluent families, whereas sewing middle-class women’s participation in the public sphere consisted of charitable sewing. They also “sustain[ed] traditional ideas of femininity” as Gordon illustrates: “Individual women and women’s aid societies made practical things like clothing, blankets, and diapers to give directly to others or fancier items like embroidered pillowcases to sell at fundraising fairs” (24). Thus, Singer’s instruction booklets, for example A Manual of Family Sewing Machines, which dates from 1914, “encouraged training on sewing machines [for working-class women and girls] as a means to get a job” (Gordon 7). As Hounshell remarks, Singer also “trained women to demonstrate to potential customers the capabilities of the Singer machine” and to “[teach] buyers or their operators how to use a sewing machine” (84-85). It is here that women taught other women about the machine, thereby appropriating knowledge of the male-connoted machine for instruction, education, and employment.

Women’s Self-Fashioning of Modernity

As much as modernity was the age of urban mass-cultural production, the era also saw “the rise of the individual,” which was closely tied to the “rise of capitalism” (Singer 30-31).18 Autonomous dress making expressed women’s individuality against uniformity of appearance. For example, they adapted patterns to individual preferences or shortened hemlines. As a means of unique and creative self-expression and self-actualization, this ‘fabrication’ of individuality in the modern urban crowd can also be viewed as women’s emancipation from established dress norms and gender expectations—particularly when wearing their individually created style in public.

Sewing allowed women to “meet community standards of fashionable and respectable appearances” (Gordon 10) since the increased public engagement was still bound to certain rules, such as gender compliant dress patterns. Women’s expression of individual style became not only “a way to dress according to the rules,” but also, viewing individuality as emancipation, “a tool for making new rules” which tests out boundaries across gender, class, and race (27, 9).

Surpassing class boundaries with this alternative consumption of fashion, sewing also enabled less affluent women to participate in the public discourse of fashion and its consumption. Pointing to the stark socioeconomic divide between producer and consumer, Gordon notes that “[t]he thousands of female operatives who worked in clothing factories and sweatshops could rarely afford the garments they made. Instead, they used their skills, and often fabric remnants from the industry, to make their own clothing at night or during slow periods at work” (10). This further blurred the boundaries between paid and unpaid production and consumption (3). With regards to socioeconomic upward stylization, working-class women thus “used sewing as a way to conform to urban middle-class standards of dress and appearance” (29). They emulated middle-class style by either copying department stores’ and magazines’ fashion designs or by using the patterns provided in respective magazines.19 As Gordon adds, advice columns in sewing magazines gave dressmaking advice to “lower-middle-class or even working-class women” who “would be the most eager for advice on how to fit in to a middle-class aesthetic” (12).

As much as marketing attempted to reinterpret or ‘recode’ the meaning of sewing machines from a means of domestic drudgery to a motorized ‘machine’ of women’s emancipatory endeavors, women’s individual experience and expression of fashion also relied upon financial means. Though it was still more affordable than ready-to-wear fashion, home dressmaking, to apply Singer’s wording, was indeed “contingent on the provision of material necessities via the marketplace” (32). Thus, women could only be the tailors of their own modern experiences of individuality and emancipation if they had the material means (e.g., fabric and a sewing machine) and skills.

Conclusion and Outlook

Analyzed as a cultural artifact in the context of gender and New York City’s machine-age modernity, the sewing machine created a bidirectional movement for women across the separate-spheres boundary. The sewing machine took up a complex and polysemic middle role between the enforcement of existing gender boundaries and a renegotiation of these boundaries. By complying with ‘feminine’ notions of domesticity, motherhood, marriage, and dependence upon the husband, the sewing machine reinforced traditional gender roles. Conversely, the sewing machine also permitted women’s entrance into the public sphere through mass cultural production and consumption, education and employment, politicization, emancipation, spatial movement, and individual expression.

As a mass cultural artifact of modernity, production, and consumption, the sewing machine’s introduction into private-sphere domesticity for home sewing blurred the separate-spheres boundary between (public) production and (private) consumption. The sewing machine therefore not only illustrates the very constructedness and fragility of modern feminine gender identity, but also of gender-based boundaries of public and private sphere in modernity. These middling positions—of women’s complex roles, as well as of the sewing machine’s polysemic nature and its inherent modern aesthetic—therefore make apparent modernity’s discourse between social acceleration and deceleration. If women ‘sewed’ modernity, the realms for their private- and public-sphere experiences became increasingly seamless.

Still, more than a hundred years after New York City’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the story of women’s modernity as ‘told’ by the sewing machine is also a story of discrimination regarding payment, working conditions, and opportunity—all of which are still highly topical with regard to the collapses of factories like Rana Plaza20 and the exploitation of women’s labor power for industrialized nations’ garment consumption. Thus, today’s fast fashion still revolves around women. Their experience of fashion production and consumption still exhibits notions of modern acceleration, efficiency (of production costs), and mobility (particularly regarding globalization and Internet shopping). Recent developments, such as the home-sewing revival, which again blurs the lines between production and consumption, expose the creative and decelerated side of the sewing machine once more and thereby also significantly draw attention to women’s predominantly (negative) experience of today’s fast-fashion discourse.

Works Cited

“175 Die in Blazing Fire-Trap; Nearly All Victims Women.” San Antonio Light and Gazette, 26 Mar. 1911, newspaperarchive.com/san-antonio-light-and-gazette-mar-26-1911-p-1/. Accessed 23 Jan. 2018.

A Manual of Family Sewing Machines. Singer Sewing Machine Co., 1914.

Adams, Katherine H., et al. Seeing the American Woman, 1880-1920: The Social Impact of the Visual Media Explosion. McFarland & Company, 2012.

Barry, Peter. Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. Manchester UP, 2017.

Barth, Gunther. City People: The Rise of Modern City Culture in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford UP, 1980.

Bender, Daniel E. “‘A Foreign Method of Working’: Racial Degeneration, Gender Disorder, and the Sweatshop Danger in America.” Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective, edited by Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald, Routledge, 2003, pp. 19-36. doi:10.4324/9780203616741.

Bender, Daniel E. and Richard A. Greenwald. “Introduction: Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Global and Historical Perspective.” Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective, edited by Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald, Routledge, 2003, pp. 1-16. doi:10.4324/9780203616741.

Benjamin, Walter. “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire.” Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings. Volume 4, 1938-1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Harvard UP, 2003.

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. U of Chicago P, 1988.

Boris, Eileen. “Consumers of the World Unite!: Campaigns against Sweating, Past and Present.” Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective, edited by Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald, Routledge, 2003, pp. 203-24. doi:10.4324/9780203616741.

Brasch, Ilka, and Ruth Mayer. “Modernity Management: 1920s Cinema, Mass Culture and the Film Serial.” Screen, vol. 57, no. 3, Autumn 2016, pp. 1-14. doi:10.1093/screen/hjw031.

Chin, Margaret M. Sewing Women: Immigrants and the New York City Garment Industry. Columbia UP, 2009.

“Composition of the Garment Industry.” Lower East Side Tenement Museum, 2005, www.tenement.org/encyclopedia/garment_composition.htm. Accessed 29 Dec. 2016.

Currid, Elizabeth. The Warhol Economy: How Fashion, Art, and Music Drive New York City. Princeton UP, 2007.

Douglas, Diane M. “The Machine in the Parlor: A Dialectical Analysis of the Sewing Machine.” The Journal of American Culture, vol. 5, no. 1, 1982, pp. 20-29. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1982.0501_20.x.

Felski, Rita. The Gender of Modernity. Harvard UP, 1995.

Gordon, Sarah A. ‘Make It Yourself’: Home Sewing, Gender, and Culture, 1890-1930. Columbia UP, 2007.

Green, Nancy L. “Sweatshop Migrations: The Garment Industry between Home and Shop.” The Landscape of Modernity: Essays on New York City, 1900-1940, edited by David Ward and Olivier Zunz, Russel Sage Foundation, 1992, pp. 213-32.

Greenwald, Richard A. “Labor, Liberals, and Sweatshops.” Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective, edited by Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald, Routledge, 2003, pp. 77-90. doi:10.4324/9780203616741.

Guglielmo, Jennifer. “Sweatshop Feminism: Italian Women’s Political Culture in New York City’s Needle Trades, 1890-1919.” Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective, edited by Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald, Routledge, 2003, pp. 185-202. doi:10.4324/9780203616741.

Helfgott, Roy B. “Women’s and Children’s Apparel.” Made in New York: Case Studies in Metropolitan Manufacturing, edited by Max Hall, Harvard UP, 1959, pp. 19-134. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674592711.c1.

Hounshell, David A. From the American System to Mass Production 1880-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States. Johns Hopkins UP, 1984.

Ickstadt, Heinz. “Die amerikanische Moderne.” Amerikanische Literaturgeschichte. J.B. Metzler, 1996, pp. 218-305. doi:10.1007/978-3-476-03535-6_5

Kelleter, Frank. “Populäre Serialität: Eine Einführung.” Populäre Serialität: Narration—Evolution—Distinktion: Zum seriellen Erzählen seit dem 19. Jahrhundert, edited by Frank Kelleter, transcript, 2012, pp. 11-48. doi:10.14361/transcript.9783839421413.11.

“The Light-Running New Home Sewing Machine: A Painful Alternative - I Will Have a New Home Machine! A New Home or a Divorce Take Your Choice Sir!.” Digital Commonwealth Massachusetts Collections Online, www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:tm70n644c. Accessed 9 Feb. 2018.

Lyman, Joseph B. The Philosophy of Housekeeping. S.M. Betts, 1867.

Marshall, Barbara L. Engendering Modernity: Feminism, Social Theory and Social Change. Polity P, 1994.

“Mother’s Helper.” Wolfsonian-Fiu Library, The Wolfsonian-Fiu, 7 Apr. 2014. wolfsonianfiulibrary.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/xc1994-753-1-01.jpg. Accessed 9 Feb. 2018.

Odencrantz, Louise C. Italian Women in Industry. Arno, 1919.

Parsons, Deborah L. Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City, and Modernity. Oxford UP, 2000.

Rosa, Hartmut. “Chapter Three: The Universal Underneath the Multiple: Social Acceleration as a Key to Understanding Modernity.” Modernity at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century, edited by Volker H. Schmidt, Cambridge Scholars P, 2007, pp. 37-61.

---. “Social Acceleration: Ethical and Political Consequences of a Desynchronized High-Speed Society.” High-Speed Society: Social Acceleration, Power, and Modernity, edited by Hartmut Rosa and William E. Scheuerman, Pennsylvania State UP, 2009, pp. 78-111.

Singer, Ben. Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts. Columbia UP, 2001.

“Sweatshops.” Lower East Side Tenement Museum, 2005, www.tenement.org/encyclopedia/garment_sweat.htm. Accessed 29 Dec. 2016.

Zhang, Li. “Bisexual and Invisible Memory: Gendered Design History of Domestic Sewing Machine, 1850-1950.” Design Histories: Tradition, Transition, Trajectories: Major or Minor Influences?, Blucher Proceedings, July 2014, pp. 177-82. doi:10.5151/despro-icdhs2014-0019.

Notes

1Rosa himself allows for an alternative conception of his idea of modern acceleration which he presents as “[f]ive forms of social deceleration” (“Chapter Three” 43).

2If women participated in this equation, it was often as a projection of “anxieties” and “fear” as existing gender hierarchies were increasingly challenged (Felski 19). Equally playing down women’s influence in and experience of modernity, women’s experience of modernity was condescendingly described by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer as one of “pleasure,” whereas men’s modernity was characterized by “rationalization” (Felski 6-7).

3Note that the separate-spheres ideology is “not so much [based on] the physical separation of the public and the domestic, but [on] their ideological separation—their separation as realms of thought and experience—and the processes which legitimate this separation” (Marshall 50, my emphasis). Women’s experience of employment in the garment factory not only resembled the hardships of domestic labor, but was often carried out under male supervision, thereby evading an oversimplified association of employment with liberation from the domestic sphere.

4Singer’s sewing machine factory was located in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, where it profited from the close proximity to New York City and its garment production sector.

5The division of labor was no modern invention but had already been discussed at the outset of the Industrial Revolution by Adam Smith in his 1776 work The Wealth of Nations.

6Dress sales increased from $473,888,000 in 1914 to $1,200,543,000 in 1919 (Gordon 14).

7For a thorough introduction to the mid-nineteenth century emergence of the urban department store as a “palace of merchandise” and “focal point for a novel form of downtown life,” see Gunter Barth’s respective chapter in City People (110-47).

8Even though working-class women had already taken up employment in premodern times, the turn of the century saw an unexpected influx of women moving into “paid jobs in manufacturing, clerical work, teaching, and nursing” (Marshall 54). Here, class stratification becomes evident: While middle-class women opted for employment in “white collar positions,” working-class women “took [on] factory and domestic jobs”—chiefly in garment production (Adams et al. 6). As Robert Bogdan notes, already at the turn of the century, “in New York City, over forty percent of clothing industry workers were women” (qtd. in Adams et al. 35).

9The sweatshop was first defined in the 1890s (Bender and Greenwald 2). In 1896, the US Department of Labor issued a definition of ‘sweating’ as: “[A] condition under which a maximum amount of work in a given time is performed for a minimum wage, and in which the ordinary rules of health and comfort are disregarded” (qtd. in Boris 204). This definition, with its tone of progressive reform, resembles the newer 1994 definition by the United States General Accounting Office of the sweatshop as a workplace “that violates more than one federal or state law governing minimum wage and overtime, child labor, industrial homework, occupational safety and health, workers compensation, or industry regulation” (qtd. in Bender and Greenwald 5). Daniel E. Bender and Richard A. Greenwald also point to an interesting shift of meaning: “[W]hen the Triangle Factory was built, it was considered a factory, the opposite of the sweatshop. Today it often serves as the archetypical sweatshop” (5-6).

10Juxtaposing the immigrant sweatshop with modernity’s emergence of the American factory, the US Industrial Commission viewed the former as a “disorderly, immoral, dangerous workplace that reflected the racial inferiority of its immigrant workers and owners” and its “lax discipline.” This set the sweatshop apart from its “clean, scientific, and orderly” American factory counterpart with its focus on efficiency, mass produce, and capitalist order (Bender and Greenwald 3).

11The name of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), established in 1900, is slightly misleading as it refers to women’s garments and by no means to an all-female workers union. Jennifer Guglielmo adds that “Jewish women workers” joined forces with “middle-class progressives and feminists in the Women’s Trade Union League” to protest against the male-led ILGWU during the ‘Uprising of the 20,000’ (186). Across class and ethnic boundaries, Greenwald views the ‘Uprising’ even as an expression of “feminist solidarity” between “middle-class reform women” and “young immigrant women” or “fragile girl strikers” (79).

12It should be noted that “unless it earned a wage, home sewing was housework, not legitimate employment” (Gordon 2).

13Toward the late nineteenth century, “parts of a piece of clothing could be mass produced [in factories] and women working at home did finishing work rather than making whole pieces of clothing from scratch,” which highlights the complex middle position of female garment workers between private (tenement) sewing and public (factory) sewing (“Composition of the Garment Industry”).

14Indicating that the sewing machine’s introduction of “[i]ncreased order” did not automatically imply “increased leisure,” Diane M. Douglas asks: “[F]or what is this ‘leisure time’ to be used?” (22).

15With home sewing as a means of subsistence instead of pleasure for many working-class women, “whether to sew was often a question of a man’s money versus a woman’s time” (Gordon 5).

16As Gordon states, Singer’s advertisements also addressed the option of installment plans when buying a new machine, so that the latter was also affordable for working-class women and, through home working, provided them with “a way to make a living in an accepted feminine line of work”—conversely implying that women’s leaving of the domestic sphere was deemed unacceptable (7). Still, a home sewing machine was expensive and thus “indicati[ve] of one’s middle class status” (Douglas 26).

17Equipped with male-produced machines, new ‘machine-women’ could ‘overpower’ men (as the New York Times editorial conveys); the ‘machine-woman’ “can also be read as the reaffirmation of a patriarchal desire for technological mastery over woman” (Felski 20, my emphasis).

18Singer describes the rise of modern individualism as owing to a new perception of “the status of the individual” which was “no longer predetermined by birth” (30). With the “rise of capitalism,” the individual began to “own [their] own labor power”—even if this was “exploit[ed],” yet also experienced “personal autonomy [from family, tribe, or commune]” (31-32).

19Initially aimed at the elite, but read by a mass market by the 1890s, a whole industry of tissue paper patterns emerged—with the best-known sewing magazines McCall; Sears, Roebuck & Co.; Vogue; Demorest; and Butterick, publishing “six million patterns annually” in the 1870s alone (Gordon 8-10).

20Even within contemporary New York City, sweatshops still exist as the Tenement Museum writes: “In 2000, it was estimated that there were 93,000 workers in the New York City garment industry. Of the shops that employed these workers, approximately 60% (7,000-7,500 shops) could be deemed sweatshops” (“Sweatshops”).