Abstract: In a historical approach, this article examines the way immigration was captured by means of a medium that was just as new and astonishing as the social upheavals brought about by modernity of which immigration itself was a key factor: photography. To this purpose, photographs taken on Ellis Island by Lewis W. Hine, one of the major photographers of his time, are described, analyzed, and interpreted. After a short introduction to the photographer’s method and approach to the subject, an in-depth analysis of four examples from his Ellis Island series shall help to elucidate in how far his visualizations of the migration process convey a remarkably wide array of factual and emotional aspects linked to this chapter of US history. Not only do the photographs give a vivid impression of the daily proceedings immigrants and officials were involved in, they also shed light on the immigrants as not merely masses of foreigners but as human beings. It is Hine’s aim of countering prevalently negative opinions and images as well as the focus on the individual immigrant experience that makes his work social photography and thus situates his photographs on the threshold between social documentation and art.

If ever a space in the perception of American culture has come to stand for migration and mobility, it is undoubtedly Ellis Island. This small island, situated right in the New York Harbor, figured likewise as the ‘island of hope’ and the ‘island of tears.’ It is somewhat surprising though that Ellis Island has in a unique fashion occupied this slot of ‘immigration station’ in our minds. Firstly, it opened relatively late in the overall period of the immigration process, when immigration from Europe had already been going on for over 200 years, and it closed its gates in 1932, after being in use for only forty years.1 This positioning as ‘immigration station’ might be due to the sheer number of immigrants that entered the country through the island: Between 1892 and 1932 more than twelve million immigrants were processed on Ellis Island. Additionally, Ellis Island owes its status as a symbol of immigration to its position as a national monument, which it was proclaimed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965. What surely adds to its iconic aura is the amount of emotionality that took place there, stemming from human tragedies, such as the separation of families and couples, rejection from immigration, and shattered hopes. The situation on Ellis Island was one of particular intensity: “Although the time spent at the island depot was usually only a few hours, the experience was, for many immigrants, the most traumatic part of their voyage to America” (Kraut 55). Finally, its standing as a landmark site of US immigration history is fortified by the island’s remarkable location within sight of the New York skyline as the ‘safe haven’ and the Statue of Liberty as the symbol of the freedom to be found in the Promised Land.

Ellis Island and its power to fascinate both Americans and non-Americans has triggered various artistic responses, for instance in the fields of literature, visual and plastic art. The following essay, however, will be concerned with just one aspect: the visualization of Ellis Island proceedings in the photography of Lewis Hine. The appeal of photographs taken on Ellis Island, today as strongly felt as at the time, derives from two sources: the novelty and unprecedented realism of the medium itself at the time as well as the borderline situation depicted in the visuals. Among the various photographers’ approaches to the subject, I chose Hine’s impressive collection of Ellis Island shots for analysis and interpretation. The samples, which depict the routine of the immigration process on Ellis Island, reveal the reformatory dimension of Hine’s photography. The purpose and achievement of his pictures exceeds the mere documentation of social facts; his Ellis Island photography can clearly be identified as social photography since it neither focuses on the exoticism of foreign faces nor reproduces stereotypes about immigrants. Rather, the photographs present immigrants as people ‘just like you and me’ and point to the hardships and challenges involved in the immigration process, as will be discussed in the following.

The Social Context of Lewis W. Hine’s Photography

Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940) had taken up photography in 1903, only one year before he was elected school photographer at the Ethical Culture School in New York City, where he had been working for three years. The first task his school assigned to him was to photograph contemporary immigrants upon their arrival on Ellis Island.

He worked at this between 1904 and 1909, and took around 200 pictures in all. The purpose of this project was to reveal the new Americans as individuals, and to counter any idea that they were the worthless scourings of Europe. Hine continued to work with such redemptive purposes in mind. (Jeffrey 159)

As will be seen in the sample figures to come, Hine’s work was not a depiction of the stereotype of ‘the immigrant’ but rather of the plurality of immigrants, granting each of the subjects individuality in a unique scenery and situation, thereby suppressing established notions of the immigrants’ inferiority.

In 1908, Hine gave up teaching and worked as a ‘social photographer’ on a professional basis. The same year, he was employed as photographer by the National Child Labor Committee, which made him travel all over the continent for over thirteen years. After the introduction of the immigration quotas, severely reducing the numbers of incoming foreigners, Hine returned to Ellis Island in 1926 to take a second series of pictures. The bulk of his overall work consists of pictures of child labor throughout the US,2 but his work also comprises widely known photographs of World War I refugees in Europe and of the construction of the Empire State Building.

Hine primarily used photography for social criticism, and is therefore often compared to Jacob Riis (1849-1914), who worked as a professional journalist and became the first central figure in the field of US-American social photography. Riis was assigned to report on the conditions in the Lower East Side of New York City, and for the first time brought in the camera to lend weight to his reporting. The 1890 book publication of Riis’s photographs, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, together with campaigns and lantern slide lectures using his photography, aroused so much indignation that some measures of social reform were taken to improve housing conditions in the New York tenement quarters (Davenport 94).

As Riis’s, Hine’s photographic work exerted a substantial reformatory impetus. In order to arouse sympathy and get reformative action under way, as many people as possible had to be reached. Social photography at the turn of the twentieth century developed a very specific visual rhetoric by combining social criticism with the relatively new medium of photography. Not only did the photographic medium allow the depiction of social abuse and inequality in a new, ‘realistic’ manner, its visual mode made it more eye-catching and interesting for the public, and its mass production for journalism permitted quite a wide circulation. In addition, documentary photographs in newspapers and magazines, in contrast to written reports on social injustice, had the advantage of being comprehensible also to those who were not (yet) fluent in the English language, namely the various immigrant groups. The photographs thus addressed a larger audience than purely verbal reporting could ever have.

Hine’s work is set in the context of the Progressive Era and its initiatives to master social dilemmas. Thus his pictures “have emerged as icons of American social history and are inextricably linked with the progressive-era social agenda” (Kaplan xvii). Covering the time span from the beginning of the twentieth century until the US’s entry into World War I, the Progressive Era was marked by increased social welfare activism. Therefore, it is often depicted as a period of charity, philanthropy, and reform, which, however, oversimplifies the matter. Historian Robert B. Westbrook, for instance, reproaches the reformers of the era for an exaggerated and naïve optimism. He detects “in progressive ideology a will to power that seeks to rescue the victims of industrialization from the depredations of evil capitalism only to subject them to the cultural hegemony of the reformers themselves” (381). The reformers of the Progressive Era are thus seen as middle-class activists. With a patronizing attitude, they aimed at looking after the poor immigrant workers in order to include them into their value system and make them indebted for the received help and thus dependent.

Another criticism that has recently been voiced is that the progressive movement was not that extensive after all. It was “not only led by a relatively narrow middle-class professional elite, but . . . , for all intents and purposes, a progressivism for old American stock whites only” (Daniels, Not Like Us 47). With regard to immigrants, this became even more momentous. Alan Trachtenberg, a US scholar in the field of photography and cultural history and author of the pivotal work Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans, points out that “reformers had been slow to awaken to the special needs and unique experiences of non-English-speaking immigrants” (“Ever” 122). Most politicians of the era, also the allegedly progressive ones, were rather contemptuous of the recent immigrants; matters of ethnic tolerance and equality did not rank foremost among the political issues of the Progressive Era:

Seen from the point of view of racial and ethnic minorities, the period could very well be called the ‘regressive era,’ a time in which things grew a little worse, a time when nativism and racism gained strength and acceptance at all levels of society. (Daniels, Not Like Us 47-48)

Neither of these points of criticism does, however, apply to Hine. He did not aim at establishing any kind of social control and rather followed the ideas of John Dewey’s philosophy. Dewey claimed that progressive reform only aimed at establishing conditions which enabled the indigent to become self-sufficient and free. This approach to progressive activism is expressed in Hine’s photographs, which always show the subjects in a respectful manner maintaining their dignity and sovereignty (Westbrook 382-84).

Insofar as Hine meant to fight “ignorance and unconcern” (Westbrook 380) with his pictures, he was clearly led by reformative intentions. Too often, attention is centered on the reformative intent of his photographs of working children and downtrodden workers in the steel industry. However, his Ellis Island series can be considered to serve reformative purposes just as well. As has been shown, immigration was not found worthy of reformative measures, and immigrants, as long as they were not (yet) an integral part of the American labor force, did generally not fall under the groups deserving of help.3 They were rather met with rejection and hostility based on prejudices. The aim of reducing such bias, as pursued by Hine’s photographs at Ellis Island, can surely be called a reformative goal and suggests a categorization of the pictures in question as social photography. Picturing the immigrants as individuals was thus just the first step on the way to reform. Hine’s photography and the Progressive Era agenda do meet when it comes to humane housing and labor conditions, for immigrants as well as US-American workers. However, as Ian Jeffrey, a British researcher and author of several books on the history of photography, points out, Hine’s work cannot simply be understood as a repertoire of pictures that document problematic conditions. Hine always put the focus on the people, the conditions came second. This characteristic situates Hine’s work on the threshold between social documentation and art.

The conditions under which Hine took his pictures on Ellis Island were all but easy. Since he was only a visitor on the island, he had to work in the midst of thousands of teeming immigrants and under time pressure, adapting to the fast rhythm of the processing of immigrants. Although his camera, a newly introduced Graflex camera, was portable and could produce precise detail and framing (Davenport 95), the usual procedure was complicated:

Amidst crowds of anxious immigrants milling about, Hine had to locate his subject, isolate him from the crowd, and set the pose—almost always, because of the language barrier, without words. He had to set up his simple 5 x 7 view camera on its rickety tripod, focus the camera, pull the slide, dust his flash pan with powder, and through his won look and gesture try to extract the desired pose and expression. With a roar of flames and sparks, the flash pan exploded, an exposure was made, and beneath the protective cloud of smoke which blinded everyone in the room Hine would pack up and leave. A second exposure was out of the question; one shot was all he had. (W. Rosenblum 12)

Despite this laborious task, Hine altogether made some two hundred plates on Ellis Island, some of which were published in the reformist organ Charities and the Commons in 1908. He numbered his studies, issued them in series, titled and captioned most of them, and dated them through 1909 (N. Rosenblum 17).

Though Ellis Island was not a new subject for journalism and pictorial representation, Hine’s approach and motivation may have been new. Hine mentions “new values” and “humanitarian interest” as factors contributing to his interest in the subject. (Stange 52)4

Hine came to Ellis Island with a commission received from his employer, and a goal set by himself. The purpose of his pictures of Ellis Island was to teach the students of the Ethical Culture School “the same regard for contemporary immigrants as they have for the Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth Rock” (N. Rosenblum 17) and to explore how immigrants experienced their arrival in the New World. Hine’s ambition and his talent account for the expressive pictures in the Ellis Island series, marked by thematic variation and compositional skill. Apart from individual and group portraits, he made a large number of shots that depicted the immigrants on their actual way into the USA, some of which will be looked at more closely in the following.

The Subject: Ellis Island Routine

The pictures chosen for the following analysis, as different as they may seem, share one feature: They represent everyday proceedings on Ellis Island. The following four pictures show the immigrants in the very moment of arriving in America: from the moment of disembarkation to their way into the Ellis Island main building, called the Great Hall, where they met interpreters, and where trunks and heavy luggage were stored. Further on, they passed doctors on the way who examined them, and arrived in the Registry Room where they were questioned, and finally, once they had the admittance cards in hand, they moved on to the money exchange and railroad ticket office. Normally, an immigrant who was not detained for any reason only spent a few hours on Ellis Island before being ferried to Manhattan, Jersey City, or Hoboken (Moreno xiii-xvii). To capture stages of this journey, Hine made full use of the storytelling qualities of photography.

The first picture (Fig. 1), called Climbing into America – Ellis Island, shows immigrants crowding on a flight of stairs. Among the many people in the picture, three men, one behind the other, stand out since they are directly facing the camera. The three men are clothed warmly; they are wearing heavy coats, hats, or fur hats. In view of the people crowding all around them, the room temperature hardly required such clothing. But, as the caption indicates, the immigrants could only bring as much as they could carry, and wearing as much as possible was a way to bring over all the clothes needed. Accordingly, the three men are carrying big suitcases or baskets; the suitcase of the man farthest to the right is stuffed so tightly that a piece of cloth is hanging out.

Apart from the fact that they are photographed while going upstairs, there is a strong sense of movement in the picture. A man in the background turns around to look for or talk to someone. Another one waves a sheet of paper. Everyone in the picture has a white sheet, most likely some registration form, in their hands. The white spots they form in the overall picture, together with the garishly white headscarf of the woman on the very right, break the darkness and monotony of the scene, creating an atmosphere of busyness and restlessness—just as one would imagine such a situation. This sense of motion reflects the very idea of mobility inherent in any migration process.

Most striking in the picture is the piercing look of the three central figures:

It is true that most of his [Hine’s] pictures are posed—his technical apparatus of stand-camera and flash tray required the subject’s cooperation—but many are posed frontally, with unmistakable eye-contact between the subject and the camera lens. Such posing, which remained one of the hallmarks of Hine’s photography, was a significant departure from the methods of conventional portraiture. It was a standing rule among pictorialists . . . to avoid direct eye-contact . . . . Otherwise, they felt, the print would look too much like a mere photograph. At Ellis Island, Hine apparently discovered for himself the unique power of frontality. (Trachtenberg, “Ever” 124)

Trachtenberg states that this very frontality leads to “a certain physical distance, corresponding to a psychological distance” (“Ever” 124) which makes it possible for the subjects to define and express themselves. Yet, one can claim that frontality, just as much as it creates distance, cuts back on distance. By establishing a direct eye contact between the subject and the lens, Hine also creates direct eye contact between the subject, i.e. the immigrant, and the picture’s viewer, i.e. the American. Looking the subject straight in the eye, the observer feels spoken to and almost seems to participate in the scene. Guiding the observer’s perception in this way, Hine at the same time manages to lessen the distance between subject/immigrant and observer/American, and thus creates conditions favorable for understanding and sympathizing with the newcomers.

The internal dialogue between the image and the accompanying text opens up a deeper layer of the picture’s conception. Hine’s choice of words for the title is notable. The immigrants are not merely ‘stepping’ into the New World, but they are “climbing,” in the literal, but also in the figurative sense of the word. The word ‘climb’ holds two major implications: It is associated with an act that requires a certain effort, and it denotes an upward movement. Photograph and title thus state that coming to and settling in the US is not easy for the immigrants, but that, once they have proved to be steadfast enough, they will be better off than in their home countries and ‘climb the social ladder.’

These implications of the title are reflected in the composition of the picture. The people on the stairs are all weighed down by their heavy bags, and they are jostling with each other, which hints at the impending struggle and competition. Still, they are (symbolically) climbing up the stairs into the Promised Land. The caption attached to the picture provides further information: The group is identified as a group of ‘new immigrants,’5 and it is explained why they are so heavily loaded. It becomes evident from the captions that patience and physical strength were among the qualities required for the immigration process.

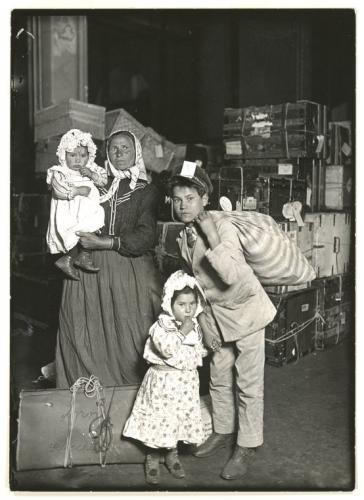

Another picture (Fig. 2) that illustrates everyday life on Ellis Island is called Italian Immigrants at Ellis Island. A family consisting of a mother, a son, a younger daughter, and a baby child is positioned against the background of piled-up luggage. Judging from their darkish complexion and peasant garb, they might originate from the rural and poor areas of southern Italy. In relation to the age of her youngest child, the mother’s face looks quite old and wrinkled, which hints at a life filled with hard work. The only accessory the woman wears is a white headscarf. Obviously, the children were purposely dressed neatly: The boy is wearing a light-colored suit, stained and creased, a tie, and a peaked cap to which the registration tag is attached, and his little sisters are wearing flowered dresses and bonnets. The mother holds the baby in her arms, the boy carries a sack which must be quite heavy, since he is weighed down by it, and has his little sister by the hand. A dented suitcase, held together by various strings and cords, is placed on the ground. All four look rather anxious; the little girl sucks her thumb, the mother and the son appear to be mistrustful.

Fig. 1. Lewis Hine, Climbing into America – Ellis Island, New York Public Library, 1905, 9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?79888>.

Original caption reads: “Here is a Slavic group waiting to get through entrance gate. Many lines like these were prevalent in the early days. There was no room to keep personal belongings, so the immigrants had to carry their baggage with them all the time” (9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?212025>).

The caption traces their vexed expressions back to the fact that some of their baggage is missing. In the bustle of Ellis Island, the loss of baggage was probably a common bother. The high piles of trunks and suitcases in the background provide the context in which the picture is to be read. Considering an average of 5,000 immigrants passing through Ellis Island per day and each of them bringing their luggage, having lost one’s baggage was not a little inconvenience. Finding lost items again among the heaps of stored luggage could take a very long time, if they were found again at all. This appears even more difficult with two underage children and a baby to attend to. Also, as immigrants usually brought with them all they possessed, losing baggage meant that basically all the family belongings, i.e. the starting capital to begin a new life with, were at stake.

What makes the family’s situation especially distressing is the father’s absence. Hine’s notes give no clue to the father’s whereabouts. He might either be dead, so the woman came over to America as a widow; or he might have been detained or even sent back, which was most commonly done for medical reasons. Another possibility is that he came to America earlier to prepare the ground for his family’s arrival, which was a widespread procedure with immigrants (Boyer et al. 568). No matter for what reason the family is incomplete in the picture, what counts is that the specific situation is considerably more difficult due to the father’s absence, especially in times when the father’s role as head of the family was still a lot more pronounced. The concerned faces are thus understandable. Even though the scene is not arranged in a melodramatic way, both the missing father and the troublesome situation make the family worth pitying. What becomes obvious is that immigration was not an easy undertaking, but that it involved many risks and obstacles the average American at the time tended to underestimate.

While the title, which is accompanied by the explanatory caption, only informs about the immigrants’ nationality, the alternative title Italian family looking for lost baggage also elucidates the immigrants’ situation. Another version of the title simply says Ellis Island group.6 With this latter title, Hine deliberately keeps contextual information from the viewer. Neither is the immigrants’ origin given, nor is the situation explained. In combination with such a title, historian Betty Bergland’s interpretation of the picture as a passage or transition photograph, representing merely “the alien” (51) from an objectifying perspective, may be accurate. She ignores, however, that Hine did provide more specific information in various titles and captions,7 and that he generally attached great importance to the additional communicative value of picture and text (Trachtenberg, Reading). Therefore, one should see photographs like Fig. 2 not only as representations of the cultural ‘Other,’ as proposed by Bergland, or as a counter image that is essentially perceived and defined as differing from one’s own cultural standard. Instead, they must be read as depictions of the cultural Other’s experience. Even though Hine did not provide a specific historical context in terms of people’s names and exact dates, his descriptive titles as well as his informative, and at times even narrative, captions lend his photographs a dynamic that by far exceeds the purely static character of “images [that] signify the universalized immigrants” (Bergland 51). Bergland’s interpretation of this photograph thus cannot be endorsed. Instead of an image showing immigrants “who have come to stand for all immigrants” (Bergland 51), it is rather a concrete re-staging of human experience.

Fig. 2. Lewis Hine, Italian immigrants at Ellis Island, New York Public Library, 1905, 9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?212029>.

Original caption reads: “Lost baggage is the cause of their worried expressions. At the height of immigration the entire first floor of the administration building was used to store baggage” (9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?212029>).

An essential factor within the Ellis Island organization was the work of interpreters. Not only were they the only ones able to mediate between immigrants and Ellis Island officials in case of problems or misunderstandings, they fulfilled the important task of interviewing the newcomers as well. All immigrants were questioned in the Registry Room during the so-called primary inspection, which resulted either in their admittance, detention and a following special inquiry, or exclusion (Moreno 193-94).

In the picture below (Fig. 3), Hine captured a typical questioning scene. The setting is a room in the Ellis Island Main Building, where a young immigrant man is standing at a high desk. At the opposite end of the desk two Ellis Island clerks, wearing uniforms and caps, are intently bent over tables and forms. The clerk on the left is the inspector;8 next to him is the interpreter. The third man is obviously waiting for them to inspect his data and immigration application. Behind him several other young male immigrants are sitting on wooden benches and watching the procedure attentively; they are either waiting to be the next ones to be checked, or, in case they came as one group, they are waiting until their companion has been inspected. All the young immigrants are tidily dressed, wearing starched shirts, ties, suits, and coats; all are shaved and have their hair cut short; altogether they make a rather well-to-do impression. Their light complexion and hair color may be an indicator of their northern or western European origin.

Fig. 3. Lewis Hine, The Interpreter Ellis Island, The George Eastman House, 1926, 9 Feb. 2009 <http://www.geh.org/fm/lwhprints/htmlsrc/m197701770038_ful.html>.

Fig. 3. Lewis Hine, The Interpreter Ellis Island, The George Eastman House, 1926, 9 Feb. 2009 <http://www.geh.org/fm/lwhprints/htmlsrc/m197701770038_ful.html>.

The composition of the picture clearly splits the subjects into two parties; a dividing line could be drawn right in the middle. On the left, the Ellis Island officials go about their daily work without looking at the man facing them, almost as if they took no notice of him; their full attention is directed to the sheets of paper in front of them. On the right, the group of immigrants direct their full attention to the officials; also the man at the desk looks at them expectantly. In view of the importance of the matter and the language barriers, full concentration on both sides was indeed indispensable. The desk almost appears to be a negotiating table, and the scene communicates an atmosphere of formality. There is also a mood of suspension and expectancy in the way the immigrants fixate the writing clerks with their eyes. The outcome of the interrogation decided whether the young man would be allowed to stay or not.

With this picture Hine not only presents one facet of the regular business on Ellis Island and one step newcomers to the US had to take, he also produces proof of the strict procedures of the immigration process. Not rarely did anti-immigration polemic complain that just about anybody who asked to be let in was indiscriminately admitted to the country. By illustrating the bureaucracy and accuracy involved in the admissions process, Hine’s picture counters such suspicions by supplying proof of thorough examination and precise filing.9

The title The Interpreter Ellis Island highlights the person of the interpreter. Although he is not prominent in the photograph but half-hidden behind the desk, Hine thus stresses his importance to the scene. In fact, the scene would not be possible without him. The interpreter is the connecting link between the American clerk and the European immigrant, between the New World and the Old World. His role as mediator makes him the central figure.

The last picture (Fig. 4) dealt with here was shot on the outside grounds of the Ellis Island immigration station. A woman in peasant-clad, composed of headscarf, coarse blouse, and apron, is shown in profile. To her right, a girl wearing a dress with a white collar and having her hair nicely done and a boy in a sailor suit are shown from behind. The only backdrop is the fence the three of them are standing in front of. The title of the picture is notable, it says: A woman, a boy and a girl at a chain link fence and does not give any indication whether they are one family or not. Either Hine himself did not know for sure whether they belonged together, which might be possible considering the language barrier mentioned above, or they are in fact just a woman, a girl, and a boy who are accidentally standing next to each other along the fence. A third possibility might be that they do belong together, but the term ‘family’ was deliberately avoided in the title. The rather lengthy enumeration of the single figures in the picture makes the reader aware of the fact that this is not a complete family but that one member, i.e. the man, is missing. The title also uses the most neutral terms—“woman,” “girl,” and “boy” instead of ‘mother,’ ‘daughter,’ and ‘son’—and thus tears the individuals from the family context as if to suggest that without the man/father, as the traditional head of the family, they are not a proper family any more.

Fig. 4. Lewis Hine; A woman, a boy and a girl at a chain link fence; New York Public Library; undated; 9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?79885>.

Fig. 4. Lewis Hine; A woman, a boy and a girl at a chain link fence; New York Public Library; undated; 9 Feb. 2009 <http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?79885>.

It is clear that since the children’s faces are not visible and the woman’s face is in shadow, the emphasis is on their poses and gestures. All three are looking through the fence into the distance; the woman and the boy have their arms extended in the same direction, clinging to the wire. The scene is marked by a profound feeling of longing. What they are yearning for can, however, only be speculated about. Assuming that they were refused access to the United States and are awaiting deportation, they are directing their eyes toward the Promised Land, the New York skyline, where, after the long passage, they are not allowed to go. In this case they are longing for their shattered dreams. In another interpretation one could assume that they are looking toward their old country, which seems even more plausible since they are turning their faces to the right of the picture, i.e. ‘eastwards.’10 The scene then implies a certain nostalgia and homesickness. Referring back to the title, one could even suppose that they are longing for the missing person. It was part of the Ellis Island routine that families were torn apart when one or more family members were denied entry. Family members who had contagious diseases were sent back home while the rest of the family, when in good health, was accepted (Kraut 58).

In view of the supposedly incomplete family constellation and the telling gesture of the hands reaching out toward the fence—a symbol of separation—this explanation seems lucid. Still, all these observations have to remain hypothetical; what can be said though without reservation is that the picture conveys a strong sense of longing. By giving his picture such an emotional load, Hine underlined that coming to America did not merely mean crossing an ocean, but that it involved unpleasant and trying experiences, such as loss, refusal, helplessness, and disappointment. He thus worked for a better understanding of the immigrants’ situation.

Conclusion

The immigrants’ odyssey did not stop at Battery Park, and Hine was well aware of this, as is testified by the numerous photographs he took of immigrants in their harsh living and working conditions in the tenement quarters. Yet, it is his Ellis Island series which best reflects the very spirit of the migration process. This is in part due to the location itself. Even though immigrants usually maintained the status of ‘immigrant’ for quite a while, if not for the rest of their lives in America, the pictures taken on Ellis Island, “whose very name has become synonymous with the immigrant experience” (Sandler 120), best convey the idea of transition from one world to another. The immigrants’ experiences, accompanied by fear and insecurity as well as pleasant anticipation, were surely most intense and unsettling at this specific stage. Ellis Island and New York City are thus the locales of pictures that are both specifically inspiring and informative.

The above reading of these photographs reveals a historical documentation of proceedings and routines, feelings of hardship, challenge, nostalgic sadness as well as hopeful happiness, an impression of motion, and the implicitly cultural dynamic—a textual density hardly to be found in documents using the written instead of the visual channel. By capturing the immigrants in this very moment and representing them as single characters in actual situations, Hine shifts the focus from the ‘type’ to the individual. As opposed to portraits by his contemporaries that tended to reinforce a certain typology and emphasize ethnic stereotypes, Hine mediates an image of the immigrants as human beings on the brink of a new, presumably better life, independent of their country of origin.

Works Cited

- Bergland, Betty. “Rereading Photographs and Narratives in Ethnic Autobiography: Memory and Subjectivity in Mary Antin’s The Promised Land.” Memory, Narrative, and Identity: New Essays in Ethnic American Literatures. Eds. Amritjit Singh, Joseph T. Skerrett, Jr., and Robert E. Hogan. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1994. 45-88.

- Bischoff, Henry. Immigration Issues. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2001.

- Boyer, Paul S., et al. The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People. 6th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008.

- Daniels, Roger. Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life. 2nd ed. New York: Perennial, 2002.

- ---. Not Like Us: Immigrants and Minorities in America, 1890-1924. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1998.

- Davenport, Alma. The History of Photography: An Overview. Boston: Focal Press, 1991.

- Goldberg, Vicky. “Lewis W. Hine, Child Labor, and the Camera.” Lewis W. Hine: Children at Work. Ed. Peter Meredith. Munich: Prestel, 1999. 7-20.

- Jeffrey, Ian. Photography: A Concise History. New York: Oxford UP, 1981.

- Kaplan, Daile. Introduction. Photo Story: Selected Letters and Photographs of Lewis W. Hine. Ed. Daile Kaplan. Washington: Smithsonian Institution P, 1992. xvii-xxxvi.

- Kraut, Alan M. The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880-1921. Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1982.

- Moreno, Barry. Encyclopedia of Ellis Island. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2004.

- Riis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York. New York: Scribner’s, 1890.

- Rosenblum, Naomi. “Biographical Notes.” Rosenblum, Rosenblum, and Trachtenberg 16-25.

- Rosenblum, Naomi, Walter Rosenblum, and Alan Trachtenberg. America and Lewis Hine. New York: Aperture, 1977.

- Rosenblum, Walter. Foreword. Rosenblum, Rosenblum, and Trachtenberg 9-15.

- Sandler, Martin W. American Image: Photographing One Hundred Fifty Years in the Life of a Nation. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989.

- Stange, Maren. Symbols of Ideal Life: Social Documentary Photography in America, 1890-1950. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1989.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. “Ever—the Human Document.” Rosenblum, Rosenblum, and Trachtenberg 118-37.

- ---. Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1989.

- Westbrook, Robert B. “Lewis Hine and the Two Faces of Progressive Photography.” Major Problems in the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. Ed. Leon Fink. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. 379-85.

Notes

1Ellis Island stopped its service as an immigration station in 1932; as a center for detained immigrants it was in use until 1954 (Daniels, Coming).

2A mere numerical juxtaposition shall put the work he has done in the field of child labor into perspective: The roughly 200 shots taken on Ellis Island seem remarkably few in comparison to over 5,000 taken for the Committee (Goldberg).

3This only holds true for help within the framework of government initiatives. While political action did seldom remedy the neediness of immigrants, private organizations and ethnic immigrant aid societies, such as the Immigrants’ Protective League or the Italian Welfare Society, took care of helpless newcomers (Bischoff).

4Before Hine’s documentary work on Ellis Island, the immigration station was already subject of journalistic reporting. However, the intent then was to “exploit the oddities” (Stange 52) of the immigrants’ looks and behavior; the tone of the reporting was rather a sensationalist one. Until the rise of photography, pictorial representations accompanying these reports came in the form of drawings and etchings.

5Immigrant groups arriving in large numbers from southern and eastern Europe in the last decade of the nineteenth century are traditionally called ‘new immigrants,’ as opposed to the earlier ‘old immigrants’ coming from northern and western Europe. Since the terms ‘old’ and ‘new immigration’ have been disputed lately and there is no common alternative terminology yet, the terms are used here, but in quotation marks to indicate the dissociation from any negative stereotypes frequently evoked by them.

6The George Eastman House gives these titles on their webpage at and <http://www.geh.org/fm/lwhprints/htmlsrc/m197701770137_ful.html> (last accessed on 9 Feb. 2009).

7In her description of the photograph, Bergland claims that the persons in the picture stand “on an undefined boardwalk” (51). However, as the original caption of the picture proves, Hine gave rather concrete information on where the shot was taken. Although his contextual information is not abundant, Bergland still does not sufficiently take it into account.

8The inspector, the one who takes notes on whether the respective immigrant is eligible for admission, and the interpreter usually worked together in the interrogation of those immigrants who could not communicate in English (Moreno 124, 112).

9Other pictures serving the same purpose show, for example, scenes of medical examination, luggage inspection, the tagging of newly arrived immigrants, or their processing at the railroad ticket office.

10In painting the left side of the picture is usually associated with the west, while the right side represents the east; for instance Albert Bierstadt’s Emigrants Crossing the Plains (1867), or John Gast’s Manifest Destiny (1872).